Monday, 19 September 2016

Liam Smith learns that courage and heart is not enough

Twice in two weeks British world champions - Kell Brook and Liam Smith - have stepped up to the elite level and come up short. Of the two a case can be made that Kell Brook does belong at the elite level, just not at middleweight; and certainly not at middleweight against the machine that is Gennady Golovkin. The Sheffield welterweight world champion's next outing at light middle will prove beyond doubt if he's as good as many of us believe he is when up against the likes of Canelo Alvarez - assuming, of course, that the Mexican stays at 154lbs to defend the WBO belt he just won from Britain's Liam Smith, against whom he looked superb, securing a 9th round stoppage on the back of a vicious left uppercut to the body.

Liam Smith, everyone agrees, is a solid fighter - brave, durable, and tough. However at the elite level those qualities by themselves are not enough. And this is where we must be honest and acknowledge that the sport in Britain suffers from a training culture that places an emphasis on conditioning at the expense of craft, skill, and the finer points of a sport that when it comes down to it has more in common with chess than chequers.

Let's look at Smith's style, which mimics almost to a tee every one of Joe Gallagher's fighters. He carries a high, tight guard, wherein his hands never leave the side of his forehead apart from when he throws a shot, typically leading with a stiff, single jab, which he throws at the same speed and with the same force. He jabs to the body but normally to the head, and when he let's more than one shot go it is usually a left-right followed by a left hook to the body, perhaps finishing with a left hook to the head. There is very little variety - either in power, speed, or range, which makes him easy to read and anticipate. At the highest level a fighter needs to vary the positioning of his hands and feet in order to confuse his opponent by constantly changing the range and distance - i.e. holding his hands away from his face shortens the distance, while also enabling him to move easier from the waist, thus allowing him to generate more power and torque in his shots, and also to roll under and slip any incoming.

The point is that a tight guard is far too restrictive and inhibits a fighter's ability to relax and throw fluid and fast combinations. It also leaves the body exposed, something that Alvarez was able to take full advantage of against Liam Smith.

Ultimately, boxing involves the generation of kinetic energy throughout a given combination of punches, with each punch adding power to the next. Joe Gallagher is a trainer who believes in a very basic style that involves very little head movement, minimal use of angles, and ring craft. His fighters arrive in top condition and rely on their superior fitness and work rate to wear down their opponents. It is a style and ethos that while lacking finesse has proved successful over the years. But it is clearly lacking when it comes up against elite opposition such as Canelo Alvarez in the case of Liam Smith, or Carl Frampton in the case of Scott Quigg.

Alvarez is a counter puncher for whom Liam Smith was tailor-made. It was staggering to see Smith throwing single jabs most of the fight while standing still, thus reducing him to stationery target against whom his opponent couldn't miss. When fighting a counter-puncher you either have to double and triple up the jab in order to deny them the space to counter while forcing them onto the back foot, or you counter the counter. What you never do is throw single jabs while standing still.

When it comes to Joe Gallagher, there's an argument to be made that his stable is too big to allow him to spend enough time on any one fighter imparting anything more than the aforementioned basics. While he is able to get them fit - and let's be honest, getting a fighter in shape is a prerequisite and a given - they all come in at the lowest common denominator in terms of style. Maybe Gallagher is incapable of teaching his fighters the finer aspects of the craft. If so it is no criticism, as he merely joins a long line of British and European trainers for whom boxing is more bludgeon than ballet.

What we saw play out when Liam Smith met Canelo Alvarez was more than a clash of styles, it was a clash of cultures. The fact that Britain currently boasts more world champions than at any other time in the history of the sport, this is not so much a testament to the quality of British boxing as an indictment of a sport that has become to so stacked with organizations and belts that the title of world champion has become increasingly devalued.

While the heart and courage Liam Smith showed against Canelo was commendable, his lack of ring craft and style was exposed. It is why he lost and lost handsomely against a fighter who himself was exposed against Floyd Mayweather Jr.

It's true what they say. In this sport it's about levels.

Sunday, 11 September 2016

Brook makes epic attempt against GGG but size matters

If ever a national anthem was suited to a fighter it is the Kazakh anthem that booms out before a Gennady Golovkin fight. It conjurs up the image of a column of tanks coming over the hill, guns blazing as they sweep all before them. The fighter known as GGG has a style redolent of said column of tanks on the offensive - merciless, relentless, and unstoppable.

Kell Brook did everything he could to withstand the middlewight champion's assault, but apart from a tremendous second round he spent the fight backpedaling like a man trying but failing to ward off a swarm of angry bees. GGG is every bit as fearsome and machine-like as his astonishing KO percentage suggests, a fighter who combines ferocious intensity with the ability to generate truly frightening torque behind his shots. Even though Brook peppered his opponent with the kind of fast and accurate combinations Golovkin hadn't encountered since he fought Willie Monroe, there was an inevitability about the result from as early as the opening salvoes of the first round, when the bigger man maneuvered Brook onto the ropes and rocked him with a thunderous left hook upstairs. It was probably this punch that fractured Brook's right eye socket, the injury which forced Dominic Ingle to throw in the towel in the second half of the fifth to prevent his fighter taking any more punishment. In doing so, Ingle's courage and compassion outside the ring matched Brook's courage inside, given the chorus of boos that greeted his intervention.

From the moment this fight was announced we knew that Brook's chance of climbing the mountain that lay in front of him would come down to his ability to hurt Golovkin with his shots while being deal with the Kazakh's incoming. Despite GGG's dismissal of Brook's power in his post-fight interviews, the IBF welterweight world champion undoubtedly rocked him with an uppercut in a second round that has to count as one of the most superb comeback rounds ever staged by a fighter given the torrid time Brook endured in the first round, previously described. It even allowed us to believe that, yes, maybe we were about to witness one of the most outstanding achievements in the ring boxing has ever produced, up there with a young Cassius Clay impetuously taking on and defeating Sonny Liston in Miami to shake up the world and claim his first world title in 1964; up there with Sugar Ray Leonard's comeback after three years out of the ring to bamboozle Mavellous Marvin Hagler in 1987; and up there, of course, with Ken Buchanan's epic performance to take the world lightweight title from Panama's Ismael Laguna over fifteen brutal rounds in the crippling heat of Puerto Rico in 1970.

But when it came to Brook's attempt to join this illustrious company the simple but iron logic implicit in the mantra that a good big man will always beat a good smaller man prevailed. Golovkin simply had too much artillery for Brook to cope with, and though immediately after the fight he was clearly upset with Dominic Ingle's decision to end the fight, in time he will surely come round to accepting that his trainer did the right thing at the right time.

Many fans, and not a few commentators, trainers and other fighters, had from the outset dismissed the fight as a mismatch due to the weight difference involved. But any criticism in this regard should not fall on the shoulders of Brook, Golovkin, or their respective teams. It should fall on the shoulders of the so-called elite fighters in and around their respective weight divisions who have steadfastly refused to take on the challenge posed by both men in the ring. It reflects the inherent weakness of the business-side of the sport, especially when compared to MMA, the fact that in too many instances fighters and their managers and promoters have sought to over-protect their assets rather than risk them. There is no shame in losing in the ring, none whatsoever, so why this consistent reluctance to risk defeat for the sake of both the sport and your own reputation as an athlete willing to test yourself against the very best?

That being said, the courage required to stand in front of the steam train that is Gennady 'GGG' Golovkin is of the uncommon kind, which is why the plaudits that have fallen on Kell Brook in both the run-up and aftermath of the fight are entirely justified. He risked all in order to win all and his failure to succeed, given the manner of his performance, has increased rather than diminished his stature. Clearly he will not be fighting at welterweight again, which immediately opens up the tantalising prospect of future fights against the likes of Canelo Alvarez, Miguel Cotto, and Britain's Liam Smith.

As for Golovkin, he says that he wants Billy Joe Saunders' WBO middleweight belt in order to unify the title. There is also the possibility of finally making a fight against Chris Eubank Jr happen. However it has to be said, after watching him take apart a previously undefeated Kell Brook, that neither Saunders nor Eubank Jr will be entitled to feel confident of doing what 36 others have thus far failed to when it comes to put a dent in the Kazakh's armour.

Sheffield's Kell Brook proved against GGG that in boxing courage and skill isn't everything. Size really does matter.

Kell Brook did everything he could to withstand the middlewight champion's assault, but apart from a tremendous second round he spent the fight backpedaling like a man trying but failing to ward off a swarm of angry bees. GGG is every bit as fearsome and machine-like as his astonishing KO percentage suggests, a fighter who combines ferocious intensity with the ability to generate truly frightening torque behind his shots. Even though Brook peppered his opponent with the kind of fast and accurate combinations Golovkin hadn't encountered since he fought Willie Monroe, there was an inevitability about the result from as early as the opening salvoes of the first round, when the bigger man maneuvered Brook onto the ropes and rocked him with a thunderous left hook upstairs. It was probably this punch that fractured Brook's right eye socket, the injury which forced Dominic Ingle to throw in the towel in the second half of the fifth to prevent his fighter taking any more punishment. In doing so, Ingle's courage and compassion outside the ring matched Brook's courage inside, given the chorus of boos that greeted his intervention.

From the moment this fight was announced we knew that Brook's chance of climbing the mountain that lay in front of him would come down to his ability to hurt Golovkin with his shots while being deal with the Kazakh's incoming. Despite GGG's dismissal of Brook's power in his post-fight interviews, the IBF welterweight world champion undoubtedly rocked him with an uppercut in a second round that has to count as one of the most superb comeback rounds ever staged by a fighter given the torrid time Brook endured in the first round, previously described. It even allowed us to believe that, yes, maybe we were about to witness one of the most outstanding achievements in the ring boxing has ever produced, up there with a young Cassius Clay impetuously taking on and defeating Sonny Liston in Miami to shake up the world and claim his first world title in 1964; up there with Sugar Ray Leonard's comeback after three years out of the ring to bamboozle Mavellous Marvin Hagler in 1987; and up there, of course, with Ken Buchanan's epic performance to take the world lightweight title from Panama's Ismael Laguna over fifteen brutal rounds in the crippling heat of Puerto Rico in 1970.

But when it came to Brook's attempt to join this illustrious company the simple but iron logic implicit in the mantra that a good big man will always beat a good smaller man prevailed. Golovkin simply had too much artillery for Brook to cope with, and though immediately after the fight he was clearly upset with Dominic Ingle's decision to end the fight, in time he will surely come round to accepting that his trainer did the right thing at the right time.

Many fans, and not a few commentators, trainers and other fighters, had from the outset dismissed the fight as a mismatch due to the weight difference involved. But any criticism in this regard should not fall on the shoulders of Brook, Golovkin, or their respective teams. It should fall on the shoulders of the so-called elite fighters in and around their respective weight divisions who have steadfastly refused to take on the challenge posed by both men in the ring. It reflects the inherent weakness of the business-side of the sport, especially when compared to MMA, the fact that in too many instances fighters and their managers and promoters have sought to over-protect their assets rather than risk them. There is no shame in losing in the ring, none whatsoever, so why this consistent reluctance to risk defeat for the sake of both the sport and your own reputation as an athlete willing to test yourself against the very best?

That being said, the courage required to stand in front of the steam train that is Gennady 'GGG' Golovkin is of the uncommon kind, which is why the plaudits that have fallen on Kell Brook in both the run-up and aftermath of the fight are entirely justified. He risked all in order to win all and his failure to succeed, given the manner of his performance, has increased rather than diminished his stature. Clearly he will not be fighting at welterweight again, which immediately opens up the tantalising prospect of future fights against the likes of Canelo Alvarez, Miguel Cotto, and Britain's Liam Smith.

As for Golovkin, he says that he wants Billy Joe Saunders' WBO middleweight belt in order to unify the title. There is also the possibility of finally making a fight against Chris Eubank Jr happen. However it has to be said, after watching him take apart a previously undefeated Kell Brook, that neither Saunders nor Eubank Jr will be entitled to feel confident of doing what 36 others have thus far failed to when it comes to put a dent in the Kazakh's armour.

Sheffield's Kell Brook proved against GGG that in boxing courage and skill isn't everything. Size really does matter.

Saturday, 27 August 2016

Both Irish, both world champions, so why is Conor McGregor more famous than Carl Frampton?

Like millions around the world, I enjoy watching Conor McGregor. The guy possesses true star quality; he's articulate, funny, confident, arrogant (in a good way) - all of it combined in a package that makes for great entertainment. Moreover, after his recent victory in his rematch with Nate Diaz, he's also as tough and as brave as they come.

Yet considering the limitations of MMA when compared to boxing - i.e. brutal instead of beautiful, clumsy rather than clinical, a sport in which it is the attributes of the ploughhorse rather than the racehorse that hold sway - it has to count as a travesty that Conor McGregor is the world's best known fighting Irishman, unable to walk down any high street or main street in the Western world without being recognised, while Carl Frampton could conceivably stand outside his local supermarket for an hour or two and not be given a second look.

This gulf in profile between two professional fighters from the same island, both of whom are world champions, is not a judgment on the qualities of both sports - how could it be given that boxing is the far superior of the two? It is, however, an indictment of the lack of integrity when it comes to the money side of boxing in relation to its surplus when it comes to MMA. To put it plainly, where the UFC treats MMA fans as more than ticket and PPV fodder, the people in control of boxing have a tendency to do precisely the opposite. The result is that MMA has been allowed to occupy much of the space previously dominated by boxing when it comes to spectator interest and mainstream recognition, and losing far too many fans to its MMA rival as a result.

Just consider that magical era of great heavyweight contests of the sixties and seventies, when the best fought the best - and more than once. Does anyone seriously believe that if those legendary names - Ali, Bonavena, Chuvalo, Patterson, Liston, Frazier, Foreman, Norton, etc. - were fighting today that they'd be allowed to fight one another until the very last dollar bill had been wrung out of fights against lesser opposition? Or how about the great middleweight era of the 1980s, when the Four Horsemen - Leonard, Hagler, Hearns, and Duran - went to war against once another when they were still in their prime? The aforementioned ring greats did not place a priority on preserving an unbeaten record, nor did they go out of their way to take the easy route to the top. By doing things the hard and right way they developed and improved in ways they would never have otherwise.

Now fast forward to the highly anticipated fight between Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquaio in 2015. One thing on which every boxing fan, commentator and writer was agreed was that it was a fight that should have happened six or seven years before it did, when both fighters were in their prime, especially Pacquaio whose decline was self evident throughout a contest that did much to turn off even the most ardent follower of the sport. As for Mayweather, towards the end of his career we are talking one of the most risk averse world champions boxing has seen, focused on protecting and preserving his 'O' regardless of the quality of opposition he opted to face in the process. It was boxing as business rather than supreme test of courage, skill, movement, and will. Not that Mayweather's legacy is one to be sniffed at. As a fighter he was playing chess while his opponents were playing chequers, which meant he was hardly ever forced out of second gear. But unlike Conor McGregor vis-a-vis Nate Diaz, Mayweather never looked at a mountain in the shape of a Golovkin and felt the urge to climb it. Even when he fought Canelo he made sure it was at a catchweight that ensured the Mexican's biggest fight was not the one that unfolded in the ring but one he was forced to conduct against the scales before he stepped through the ropes.

Boxing is in desperate need of its own Dana White to clean house and reassert the primacy of the action inside the ring between the fighters over the deals and horsetrading that takes place outside between promoters and managers. The plethora of boxing sanctioning bodies have only served to diminish the status attached to a world title, while the control exerted by promoters has over time denuded the sweet science of much of its cachet value.

Something has to be done and done quickly, else a fighter of Carl Frampton's undoubted quality risks continuing to stand criminally unrecognised outside that supermarket while his compatriot, Conor McGregor, swaggers up and down the Vegas Strip like he owns the place.

Friday, 19 August 2016

Emile Griffith's struggle for respect in a man's world

It was hard enough being black in America in the 1950s and ’60s, forced to endure a daily assault on your dignity, humanity, and at times even your life. Imagine, then, what it was like to be black and gay at a time when homosexuality was a criminal offence. Then consider the particular challenges involved in being black, gay, and a boxing world champion to boot.

“God breaks those he wants to make great.”

This biblical aphorism could have been written with the remarkable life of Emile Griffith in mind. His 112 professional fights, stretching 19 years from his ring debut in 1958 to his last fight in 1977, after which he finally accepted that he had “nothing more to prove,” could never come close to competing with the struggle against adversity he fought on the other side of the ropes. For Griffith, a man whose ambition in life as a young man was never to win fame and fortune in the hurt business but to make ladies’ hats, the ring was not an arena where men risked all but rather a sanctuary and an escape from the constant pressure of concealing who he really was when he wasn’t in the gym preparing for a fight or in the ring proving himself. Award-winning sportswriter Donald McRae’s new biography of the five-time world welterweight and middleweight champion, A Man’s World, is suffused with the respect that befits someone who fought more world championship rounds, an unbelievable 337, than any other fighter in the sport — “51 more than Sugar Ray Robinson and 69 more than Muhammad Ali,” the writer informs us.

But as bad as things were outside the ring, tragedy was no stranger to Griffith in it either. Here he will forever be known for his brutal third fight against Benny “The Kid” Paret at Madison Square Garden on 24 March 1962. It was for the welterweight title that Paret had wrested from Griffith in their previous encounter and was destined to be an ugly affair from the day the contracts were signed. Paret and his team spared no opportunity to ridicule the Griffith over his sexuality, which by then was the worst-kept secret in a sport that wore its machismo as an antidote to the emasculating truths of polite society.

The insults, veiled and not so veiled, reached their nadir at the weigh-in, when in front of the large crowd of witnesses, including the press, the dread-word “maricon” (faggot) issued from Paret’s lips. As McRae describes it: “The sour taste of humiliation rose up in Emile’s throat like bile.” From that moment at stake was more than a championship belt. Now it was a matter of honour and a fight that Emile Griffith could not and would not allow himself to lose. Paret was going to pay and pay dearly, with fight night destined to be his last. During a predictably bruising war of attrition the Cuban finally succumbed in the 12th round to a barrage of unanswered right hands while slumped against the ropes, before the referee finally stepped in to stop it. It was too late. Paret never recovered. He slipped into a coma and died in hospital a week later.

Griffith never got over Paret’s death, which continued to haunt him in recurring nightmares right up to the day he died in 2013. However he had many mouths to feed and no other way of doing it than in the ring. And so he fought on — though never with the same intensity or bad intentions as before.

When he wasn’t fighting or getting ready to fight, Griffith was a regular in the underground scene of gay bars and clubs located then around New York’s Times Square. It was the only time he could relax and be himself, surrounded by friends and acquaintances that adored him. He was their champion and they protected him, made him feel there was nothing to fear or be ashamed of.

This was at a time in the early ’60s when, as McRae writes, “gay men and lesbians could be dismissed from their jobs or denied housing and other benefits on the grounds of sexuality. Their persecution was often undertaken most aggressively and systematically in New York, supposedly the country’s most liberated city.” It was a time when “over a hundred men a week were entrapped for ‘solicitation’ by undercover police, and when moral panic was regularly whipped up by ambitious politicians using the morality card in order to garner votes from a prurient and hypocritical public.”

Yes, indeed, it was no time to be gay in New York or anywhere else in the land of the free.

Even in more enlightened times, when after many years of struggle for justice homosexuality won its rightful acceptance within mainstream society, the danger had not completely passed. Griffith found this to his cost in 1992 when emerging from a gay bar in New York, he was set upon by a gang of bigots and beaten to within an inch of his life.

It was in the ring where Emile Griffith punctured the myth of and masculine stereotype that drew a false equivalence between cowardice, weakness and homosexuality. He fought all over the world under the tutelage of his close friend the legendary trainer Gil Clancy, who never left his side through good times and bad.

Towards the end of his career, in 1975, when he was reduced to fighting for a fraction of the money he could once command, Griffith took a fight in Soweto, the iconic black township in what was then apartheid South Africa. Griffith had been expecting conditions similar to those that had faced blacks in the Deep South during Jim Crow. What he found was far worse. When told by the promoter, who’d been contacted by a government official, that Clancy would not be allowed in his corner, due to apartheid laws which meant the only white men allowed in the arena in Soweto for the fight would be the police, the referee, and three judges at ringside, Griffith finally cracked. No Clancy, no fight, he informed the promoter.

The former world champion’s refusal to fight made newspaper headlines, but there was nothing to be done. The head of South Africa’s boxing board of control announced they could not intervene, but that perhaps a compromise could be reached.

Griffith responded thus: “I don’t believe in this law, and I am not negotiating. I tell you one thing straight — no Clancy, no fight. You can lock me up or send me home. I know what’s right and wrong. And this law is wrong. I refuse it.”

The fight went ahead with Gil Clancy in Griffith’s corner.

It was in 2008 that Emile Griffith was finally able to find the words to articulate the horrible hypocrisy that he was forced to bear throughout his life due to his sexuality. He told his friend, the reporter Ron Ross: “I keep thinking how strange it is. I kill a man and most people forgive me. However I love a man and many say this makes me an evil person.”

A moving epitaph to the Emile Griffith story occurred in Central Park on a winter’s afternoon in 2004, when Griffith met Benny Paret’s son, Benny Paret Jnr, who was still to be born when his father died as a result of that brutal encounter in 1962 at Madison Square Garden. The moment was caught on film for a documentary that was being made on the tragedy. Griffith approached the pre-arranged meeting place, his gait by now was that of an old man who’d had one too many ring wars, while Benny Paret Jnr stood watching him, tentative and unsure. They exchanged a few words then hugged and cried, united in the pain of a tragedy that had marked both their lives forever after.

A Man’s World by Donald McRae is published by Simon & Schuster.

“God breaks those he wants to make great.”

This biblical aphorism could have been written with the remarkable life of Emile Griffith in mind. His 112 professional fights, stretching 19 years from his ring debut in 1958 to his last fight in 1977, after which he finally accepted that he had “nothing more to prove,” could never come close to competing with the struggle against adversity he fought on the other side of the ropes. For Griffith, a man whose ambition in life as a young man was never to win fame and fortune in the hurt business but to make ladies’ hats, the ring was not an arena where men risked all but rather a sanctuary and an escape from the constant pressure of concealing who he really was when he wasn’t in the gym preparing for a fight or in the ring proving himself. Award-winning sportswriter Donald McRae’s new biography of the five-time world welterweight and middleweight champion, A Man’s World, is suffused with the respect that befits someone who fought more world championship rounds, an unbelievable 337, than any other fighter in the sport — “51 more than Sugar Ray Robinson and 69 more than Muhammad Ali,” the writer informs us.

But as bad as things were outside the ring, tragedy was no stranger to Griffith in it either. Here he will forever be known for his brutal third fight against Benny “The Kid” Paret at Madison Square Garden on 24 March 1962. It was for the welterweight title that Paret had wrested from Griffith in their previous encounter and was destined to be an ugly affair from the day the contracts were signed. Paret and his team spared no opportunity to ridicule the Griffith over his sexuality, which by then was the worst-kept secret in a sport that wore its machismo as an antidote to the emasculating truths of polite society.

The insults, veiled and not so veiled, reached their nadir at the weigh-in, when in front of the large crowd of witnesses, including the press, the dread-word “maricon” (faggot) issued from Paret’s lips. As McRae describes it: “The sour taste of humiliation rose up in Emile’s throat like bile.” From that moment at stake was more than a championship belt. Now it was a matter of honour and a fight that Emile Griffith could not and would not allow himself to lose. Paret was going to pay and pay dearly, with fight night destined to be his last. During a predictably bruising war of attrition the Cuban finally succumbed in the 12th round to a barrage of unanswered right hands while slumped against the ropes, before the referee finally stepped in to stop it. It was too late. Paret never recovered. He slipped into a coma and died in hospital a week later.

Griffith never got over Paret’s death, which continued to haunt him in recurring nightmares right up to the day he died in 2013. However he had many mouths to feed and no other way of doing it than in the ring. And so he fought on — though never with the same intensity or bad intentions as before.

When he wasn’t fighting or getting ready to fight, Griffith was a regular in the underground scene of gay bars and clubs located then around New York’s Times Square. It was the only time he could relax and be himself, surrounded by friends and acquaintances that adored him. He was their champion and they protected him, made him feel there was nothing to fear or be ashamed of.

This was at a time in the early ’60s when, as McRae writes, “gay men and lesbians could be dismissed from their jobs or denied housing and other benefits on the grounds of sexuality. Their persecution was often undertaken most aggressively and systematically in New York, supposedly the country’s most liberated city.” It was a time when “over a hundred men a week were entrapped for ‘solicitation’ by undercover police, and when moral panic was regularly whipped up by ambitious politicians using the morality card in order to garner votes from a prurient and hypocritical public.”

Yes, indeed, it was no time to be gay in New York or anywhere else in the land of the free.

Even in more enlightened times, when after many years of struggle for justice homosexuality won its rightful acceptance within mainstream society, the danger had not completely passed. Griffith found this to his cost in 1992 when emerging from a gay bar in New York, he was set upon by a gang of bigots and beaten to within an inch of his life.

It was in the ring where Emile Griffith punctured the myth of and masculine stereotype that drew a false equivalence between cowardice, weakness and homosexuality. He fought all over the world under the tutelage of his close friend the legendary trainer Gil Clancy, who never left his side through good times and bad.

Towards the end of his career, in 1975, when he was reduced to fighting for a fraction of the money he could once command, Griffith took a fight in Soweto, the iconic black township in what was then apartheid South Africa. Griffith had been expecting conditions similar to those that had faced blacks in the Deep South during Jim Crow. What he found was far worse. When told by the promoter, who’d been contacted by a government official, that Clancy would not be allowed in his corner, due to apartheid laws which meant the only white men allowed in the arena in Soweto for the fight would be the police, the referee, and three judges at ringside, Griffith finally cracked. No Clancy, no fight, he informed the promoter.

The former world champion’s refusal to fight made newspaper headlines, but there was nothing to be done. The head of South Africa’s boxing board of control announced they could not intervene, but that perhaps a compromise could be reached.

Griffith responded thus: “I don’t believe in this law, and I am not negotiating. I tell you one thing straight — no Clancy, no fight. You can lock me up or send me home. I know what’s right and wrong. And this law is wrong. I refuse it.”

The fight went ahead with Gil Clancy in Griffith’s corner.

It was in 2008 that Emile Griffith was finally able to find the words to articulate the horrible hypocrisy that he was forced to bear throughout his life due to his sexuality. He told his friend, the reporter Ron Ross: “I keep thinking how strange it is. I kill a man and most people forgive me. However I love a man and many say this makes me an evil person.”

A moving epitaph to the Emile Griffith story occurred in Central Park on a winter’s afternoon in 2004, when Griffith met Benny Paret’s son, Benny Paret Jnr, who was still to be born when his father died as a result of that brutal encounter in 1962 at Madison Square Garden. The moment was caught on film for a documentary that was being made on the tragedy. Griffith approached the pre-arranged meeting place, his gait by now was that of an old man who’d had one too many ring wars, while Benny Paret Jnr stood watching him, tentative and unsure. They exchanged a few words then hugged and cried, united in the pain of a tragedy that had marked both their lives forever after.

A Man’s World by Donald McRae is published by Simon & Schuster.

Tuesday, 16 August 2016

Whither Manny Pacquaio?

News of Manny Pacquaio's return to the ring induces sadness rather than gladness, exacerbated by the commendably frank admission by the 37-year old that the main motivation for coming back is financial. In a perfect world ring legends retire gracefully while still at the top of the sport and with the kind of financial security a successful career in boxing fully deserves. But we do not live in such a world, with Pacquaio's imminent comeback so soon after retirement yet another example of how the sweet science devours its own more often than not. It

The fight upon which Pacquaio should have retired, and upon which his legacy should have depended, was the Mayweather fight in 2015. Sadly, Manny's performance against Mayweather was so disappointing that rather than cement his legacy, it merely confirmed that he was a pale imitation of the machine that used roll over his opponents one after the other. The attempt to excuse his performance with the claim he was carrying a shoulder injury picked up in training camp, well, let's just say that it was akin to witnessing superman blaming his failure to save the world on a sore finger.

In truth is Manny Pacquiao's glory days were over well before 2015. His reign as one of the greats of his era came to a shuddering end at the hands of Juan Manuel Marquez, his ring nemesis, in the sixth round of their fourth meeting on December 8, 2012, when the Filipino southpaw walked into the kind of right hand that ends careers, in some cases lives, in an instant. The sight of him lying inert on the canvas afterwards is not one that makes a strong case for professional boxing being considered a legitimate sport.Not that there was any shame in losing to Jean Manuel Marquez. On the contrary, the Mexican was the one fighter who had Pacquiao’s number and he arguably should have won three of their four fights. Instead he lost two, drew one and won the last. They fought 42 rounds in total, which count among the most competitive ever fought in the sport.

But Pacquiao’s career cannot be judged by the Marquez fights alone. In his prime he was, as said, a ferocious fighting machine who combined frightening and fearsome power with relentless aggression. His partnership with Freddie Roach at Roach's famed Wildcard Gym in Hollywood saw them both reach the heights in their respective trades; Pacquiao recording some immense performances that will be held up as examples of excellence in years to come. The golden period of his career took place between 2006 and 2009, when the fighter affectionately known as Pacman was invincible, dispatching the likes of Erik Morales, Jorge Solis, Marco Antonio Barrera, David Diaz, Oscar De La Hoya, Ricky Hatton and Miguel Cotto. His popularity reached a new level of superstardom, especially back in The Philippines, where he was a national hero. A backstory made up of a childhood spent in extreme poverty in General Santos City only cemented his status as a people’s champion, the most meaningful title that any fighter could ever hope to achieve.

In this regard Pacquiao never forgot his beginnings or those he left behind, donating a huge proportion of his wealth to helping the poor in a country he never left behind. Indeed, though he could have opted to leave The Philippines behind for the glitz and comfort of a gated community in the Hollywood Hills, Pacquiao spent most of his time there and, of course, went into politics in order to serve his people.

Everyone knows the Mayweather fight should have happened six years before it finally did, when they were both at their peaks. The ocean of bad blood between Mayweather and his old promoter, Bob Arum, who oversaw Pacquiao’s career, ensured it never did, leaving a gap in their records that was only filled in 2015. The fight, when it came, was a crushing anti-climax, involving a way below par Pacquiao failing to force his opponent out of second gear. Regardless, despite his poor performance against Floyd, Pacquiao’s career possessed more meaning for more people than Mayweather’s ever could.

Unlike a fighter who consistently outdid himself in plumbing the depths of vulgarity in flaunting his wealth, Pacquiao fought for the have nots — the legion of migrants who make up the cleaners, valets, busboys and day labourers in the land of the free, those who exist on the flip side of the Vegas Strip, with its swanky hotels, casinos and restaurants.

Every time he stepped into the ring the Filipino carried their hopes and dreams, providing them with a temporary respite from their worries and woes, allowing them to enjoy the vicarious thrill of a champion who was of them and like them being exalted and respected in a culture in which their existence was barely acknowledged much less respected.

The Filipino champion was a symbol of pride in a world of injustice.

In this regard his greatness is unsurpassed and is why, though I wish him well, I will not be able to bring myself to watch his comeback fight against Jessie Vargas in November. As Smokin' Joe Frazier said, "Life doesn't run away from nobody. Life runs at people." Sadly, life, once so sweet, is now running at Manny Pacquaio.

Tuesday, 9 August 2016

When Ken Buchanan was King of Madison Square Garden

Not many fighters can claim to have held the unofficial title of King of Madison Square Garden during their careers. The acknowledged Mecca of boxing, New York’s Madison Square Garden in its heyday was an arena where even the most accomplished of champions and contenders were liable to be overwhelmed by the pressure of occupying its hallowed terrain. And many found themselves leaving the ring to a chorus of boos from the most hard-to-please-fans in the world in response to a lacklustre performance.

Madison Square Garden became synonymous with the sport of boxing in the over 100 years and four different locations in which it has hosted some of the most epic contests in the history of the fight game, involving the likes of John L Sullivan, Rocky Marciano, Sugar Ray Robinson, Jake La Motta, Muhammad Ali, Jerry Quarry, Joe Frazier, Roberto Duran, and Sugar Ray Leonard.

But of all the legends who’ve garnered a place in The Garden’s illustrious history, Scotland's Ken Buchanan deserves a special mention having topped the bill there not once, not twice, but a remarkable five times.

During the early 1970s, the Scottish lightweight brought to the ring the elegance of a ballerina and the heart of a pitbull. A piston jab so accurate it could have been the prototype upon which precision guided missiles were based was complemented by the contortions of an escape artist in the way he could frustrate even the most skilled attempts to lay a glove on him. It was a combination that saw him win the world title from Panama’s Ismael Laguna in 1970 over fifteen brutal rounds in the murderous heat of an outdoor arena in San Juan, Puerto Rico. In a display of guts and tenacity that even today still ranks as one of the most outstanding in the history of the ring, Buchanan announced his arrival onto the world stage.

His first appearance at The Garden in his trademark tartan shorts came just three months later in December of the same year, when the newly crowned champion fought Canadian welterweight contender Donato Paduano in a ten round non-title fight. Giving away ten pounds in bodyweight to his heavier opponent, the Scot lit up the crowd to such an extent that it rose more than once in a standing ovation in appreciation of the wonderful artistry he displayed in the process of taking his opponent to school. Watching the fight today, Buchanan ducking and weaving to avoid Paduano's punches, at times it almost appears his upper body is attached to his legs by a ball and socket instead of flesh and bone. Indeed at points during the contest he dips his head so low he could untie the laces on the Canadian's boots. In the end Buchanan emerged a comfortable winner with a unanimous decision.

His next outing at The Garden came almost exactly a year after wresting the title from Laguna, when the two met for a widely anticipated rematch. Buchanan had already defended his title twice in the interim, and by the time he stepped into the ring to meet his old rival he’d established himself as the undisputed champion. It was a contest that took on the same pattern as the first fight, with the Scotsman keeping his jab in the Panamanian’s face for fifteen rounds to win yet another unanimous decision in front of a full house.

Another Panamanian in the shape of a young Roberto Duran was Buchanan’s next challenger. Duran may have only been emerging as the legend he was to become, but already he possessed a reputation for destroying his opponents with a relentless come-forward style, throwing bombs.

The Panamanian's fight against Ken Buchanan on June 26, 1972, remains one of the most controversial The Garden has ever hosted. It began at a blistering pace, when from the opening bell Duran jumped on the Scotsman with the objective of denying him the use of a jab that by then was considered the best in the business. Duran's gameplan paid off, as within a minute of the fight Buchanan was forced to touch the canvas at the end of a right hook to take a standing eight count. If he didn’t know it already, the world champion knew now he was in for a long night.

Back he came though, trading combinations with the challenger in an attempt to keep him at bay. It was in this fashion the contest continued over thirteen bruising rounds in which Duran’s head rarely left the champion’s chest, so intent was he on fighting on the inside. The low blow that concluded proceedings came after the bell rang at the end of the thirteenth. The resulting controversy continues to be the subject of debate among boxing fans to this day. More importantly, it still rankles with Buchanan himself, who's revealed more than once in interviews that he's still reminded of it by an occasional shooting pain through the groin.

Ken Buchanan fought twice more at The Garden, recording victories against former three time world champion Carlos Ortiz and then South Korea’s Chang-Kil Lee.

His career thereafter followed the all too familiar pattern of slow but steady decline, until his eventual retirement in 1982. Nonetheless the former lightweight world champion will forever be remembered as a true ring legend and one of only a select few to ever hold the unofficial title of King of Madison Square Garden. It's one title that no one can ever take away from him - not even with a low blow.

Labels:

Boxing,

Ken Buchanan

Saturday, 6 August 2016

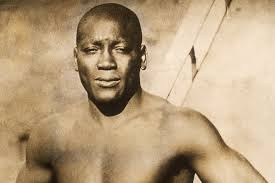

Jack Johnson - the man who wasn't afraid of anybody

On March 31 1878 in Galveston Texas a man was born who was to have a profound impact not only on the sport of boxing but on America. His name was Jack Johnson.

To be born black in late 19th and early 20th century America was to be destined for a future of low income menial jobs and the status of second class citizen at the hands of the dominant white society. It was even worse in the Deep South, where the lynching of young black men for even minor infractions of a racial divide that was as rigid as it was cruel, were a regular occurrence, it could also mean a death sentence.

Johnson’s parents were former slaves, his father Henry of direct African descent, and both worked long hours to support their six children. Jack was their second child and most of what little education he received was provided at home, where he learned to read and write. School he only attended sporadically until starting work as a labourer on the waterfornt in his early teens.

Johnson’s introduction to prizefighting came during this period, when he began taking on fellow workers and local hard men in specially organised match ups for the money offered by spectators in return for a good fight.

It has also been suggested that he participated in what were known as ‘battle royals”, a racist spectacle which involved several black men fighting one another at the same time in blindfolds. The last man standing again won a collection that was paid by the spectators in attendance.

The exact number of fights which Johnson had during his career remains under dispute, due to the fact that in his day boxing was still largely an underground sport that was illegal in many parts of the US. The least number of fights cited for him is 77, with other sources stating he fought over 100 times. Considering that boxing bouts in the early part of the 20th century could go on for thirty rounds and more, there is no disputing the immense physical ordeal he endured in a career which ended in 1938, when following the sad song of most former champions a TKO in the seventh round against an opponent who at one time would not have been fit to lace his gloves finally brought the curtain down.

But what makes Jack Johnson, who went by the fighting name the Galveston Giant, such a major figure in American sporting and cultural history was not only his undoubted boxing ability, but more a personality that brooked no deference to the prevailing racial hierarchy, one that expected blacks like him to know their place. In this he was a forerunner of another brash young black heavyweight by the name of Muhammad Ali, who cited Jack Johnson as an early inspiration.

After spending years being denied an opportunity to fight for the heavyweight title due to the colour of his skin, Johnson’s chance finally came against the Canadian holder, Tommy Burns, in 1908. Burns had taken over the title from Jim Jeffries, who’d retired and who as the champion had continually spurned Johnson’s attempts to fight for his title. Regardless, getting Burns to face him had involved two years of Johnson chasing the Canadian around the world taunting him in the press before he finally relented and agreed to face him. The fight took place in Sydney, Australia in front of a hostile crowd of 20,000 spectators.

In winning the title from Burns, even Johnson was unprepared for the wave of racial hatred that was unleashed throughout his home country. At the time the heavyweight title was deemed the preserve of white fighters, and Johnson attracted the enmity it seemed of every sector of society except his own. Even so called socialists such as famed novelist, Jack London, called for a white champion to wrest the title back from Johnson, thus spawning the era of the ‘Great White Hope’, a phrase that continues to be part of the lexicon of sports to this day.

Johnson was forced to fight a series of white contenders as the boxing establishment set out to find a white contender who would prove the physical and fighting superiority of the white man over his black counterpart. Of a series of such fights Johnson took and won in 1909, the one against Stanley Ketchel has gone down in history. The fight lasted twelve hard rounds, until Ketchel connected with a right to the head which dropped Johnson to the canvas. As he got back to his feet, Ketchel moved in to finish him off. But before he could unleash another punch he was met with a right hand to the jaw from Johnson which knocked him out. According to legend, Johnson hit Ketchel so hard that some of his teeth ended up embedded in his glove.

In 1910 the biggest heavyweight fight in the history of the sport took place in Reno, Nevada in an outdoor arena specially built for the event. Billed as ‘the fight of the century’, it saw former white champion Jim Jeffries come out of his six year retirement, saying that, “I feel obligated to the sporting public at least to make an effort to reclaim the heavyweight championship for the white race. . . . I should step into the ring again and demonstrate that a white man is king of them all.”

Johnson proved both Jeffries and the white establishment wrong, however, when he knocked the former champion down twice on the way to eventual victory in the 15th round; the referee finally stopping what had been one way traffic throughout. The aftermath saw race riots erupt across the United States, with blacks being attacked at random and during which 23 were killed. Meanwhile in black communities there were celebrations, with Johnson’s victory so significant it was commemorated in prayer meetings, poetry and black popular culture.

Thereafter, dogged by an establishment that was determined to put him in his place, Johnson’s personal life saw him tried and convicted for violation of the Mann Act, which prohibited the transportation of women across state lines for immoral purposes. Johnson, perhaps as a consequence of his being so maligned and rejected by mainstream society, was a man who sought solace in the company of prostitutes, another maligned sector of society. He was fined and sentenced to prison by an all-white jury, but instead of accepting his sentence he skipped bail and fled the country to Canada, before heading to France.

For the next seven years Johnson remained outside the US, moving between Europe and South America. In that time he continued to defend his title, though only sporadically. He finally lost it to Jess Willard in Havana in 1915. Incredibly, the fight went 26 rounds before Willard finally KO’d the reigning champion.

Returning to the US in 1920, Johnson was arrested and sent to prison to serve out his sentence. A request for his posthumous pardon is currently under consideration by President Obama. An earlier request during the previous Bush administration was turned down by the US Senate.

Johnson married three times, on each occasion to a white woman. His last wife, Irene Pineau, was asked by a reporter at his funeral what she’d loved about him. She replied, “I loved him because of his courage. He faced the world unafraid. There wasn’t anybody or anything he feared.”

Jack Johnson died at the age of 68 in 1948. Perhaps his most fitting epitaph is embodied in the quote attributed to him at the end of a Jack Johnson tribute album by Miles Davis in 1970. “I’m Jack Johnson. Heavyweight champion of the world. I’m black. They never let me forget it. I’m black all right! I’ll never let them forget it!”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)