Saturday, 6 August 2016

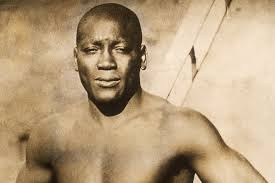

Jack Johnson - the man who wasn't afraid of anybody

On March 31 1878 in Galveston Texas a man was born who was to have a profound impact not only on the sport of boxing but on America. His name was Jack Johnson.

To be born black in late 19th and early 20th century America was to be destined for a future of low income menial jobs and the status of second class citizen at the hands of the dominant white society. It was even worse in the Deep South, where the lynching of young black men for even minor infractions of a racial divide that was as rigid as it was cruel, were a regular occurrence, it could also mean a death sentence.

Johnson’s parents were former slaves, his father Henry of direct African descent, and both worked long hours to support their six children. Jack was their second child and most of what little education he received was provided at home, where he learned to read and write. School he only attended sporadically until starting work as a labourer on the waterfornt in his early teens.

Johnson’s introduction to prizefighting came during this period, when he began taking on fellow workers and local hard men in specially organised match ups for the money offered by spectators in return for a good fight.

It has also been suggested that he participated in what were known as ‘battle royals”, a racist spectacle which involved several black men fighting one another at the same time in blindfolds. The last man standing again won a collection that was paid by the spectators in attendance.

The exact number of fights which Johnson had during his career remains under dispute, due to the fact that in his day boxing was still largely an underground sport that was illegal in many parts of the US. The least number of fights cited for him is 77, with other sources stating he fought over 100 times. Considering that boxing bouts in the early part of the 20th century could go on for thirty rounds and more, there is no disputing the immense physical ordeal he endured in a career which ended in 1938, when following the sad song of most former champions a TKO in the seventh round against an opponent who at one time would not have been fit to lace his gloves finally brought the curtain down.

But what makes Jack Johnson, who went by the fighting name the Galveston Giant, such a major figure in American sporting and cultural history was not only his undoubted boxing ability, but more a personality that brooked no deference to the prevailing racial hierarchy, one that expected blacks like him to know their place. In this he was a forerunner of another brash young black heavyweight by the name of Muhammad Ali, who cited Jack Johnson as an early inspiration.

After spending years being denied an opportunity to fight for the heavyweight title due to the colour of his skin, Johnson’s chance finally came against the Canadian holder, Tommy Burns, in 1908. Burns had taken over the title from Jim Jeffries, who’d retired and who as the champion had continually spurned Johnson’s attempts to fight for his title. Regardless, getting Burns to face him had involved two years of Johnson chasing the Canadian around the world taunting him in the press before he finally relented and agreed to face him. The fight took place in Sydney, Australia in front of a hostile crowd of 20,000 spectators.

In winning the title from Burns, even Johnson was unprepared for the wave of racial hatred that was unleashed throughout his home country. At the time the heavyweight title was deemed the preserve of white fighters, and Johnson attracted the enmity it seemed of every sector of society except his own. Even so called socialists such as famed novelist, Jack London, called for a white champion to wrest the title back from Johnson, thus spawning the era of the ‘Great White Hope’, a phrase that continues to be part of the lexicon of sports to this day.

Johnson was forced to fight a series of white contenders as the boxing establishment set out to find a white contender who would prove the physical and fighting superiority of the white man over his black counterpart. Of a series of such fights Johnson took and won in 1909, the one against Stanley Ketchel has gone down in history. The fight lasted twelve hard rounds, until Ketchel connected with a right to the head which dropped Johnson to the canvas. As he got back to his feet, Ketchel moved in to finish him off. But before he could unleash another punch he was met with a right hand to the jaw from Johnson which knocked him out. According to legend, Johnson hit Ketchel so hard that some of his teeth ended up embedded in his glove.

In 1910 the biggest heavyweight fight in the history of the sport took place in Reno, Nevada in an outdoor arena specially built for the event. Billed as ‘the fight of the century’, it saw former white champion Jim Jeffries come out of his six year retirement, saying that, “I feel obligated to the sporting public at least to make an effort to reclaim the heavyweight championship for the white race. . . . I should step into the ring again and demonstrate that a white man is king of them all.”

Johnson proved both Jeffries and the white establishment wrong, however, when he knocked the former champion down twice on the way to eventual victory in the 15th round; the referee finally stopping what had been one way traffic throughout. The aftermath saw race riots erupt across the United States, with blacks being attacked at random and during which 23 were killed. Meanwhile in black communities there were celebrations, with Johnson’s victory so significant it was commemorated in prayer meetings, poetry and black popular culture.

Thereafter, dogged by an establishment that was determined to put him in his place, Johnson’s personal life saw him tried and convicted for violation of the Mann Act, which prohibited the transportation of women across state lines for immoral purposes. Johnson, perhaps as a consequence of his being so maligned and rejected by mainstream society, was a man who sought solace in the company of prostitutes, another maligned sector of society. He was fined and sentenced to prison by an all-white jury, but instead of accepting his sentence he skipped bail and fled the country to Canada, before heading to France.

For the next seven years Johnson remained outside the US, moving between Europe and South America. In that time he continued to defend his title, though only sporadically. He finally lost it to Jess Willard in Havana in 1915. Incredibly, the fight went 26 rounds before Willard finally KO’d the reigning champion.

Returning to the US in 1920, Johnson was arrested and sent to prison to serve out his sentence. A request for his posthumous pardon is currently under consideration by President Obama. An earlier request during the previous Bush administration was turned down by the US Senate.

Johnson married three times, on each occasion to a white woman. His last wife, Irene Pineau, was asked by a reporter at his funeral what she’d loved about him. She replied, “I loved him because of his courage. He faced the world unafraid. There wasn’t anybody or anything he feared.”

Jack Johnson died at the age of 68 in 1948. Perhaps his most fitting epitaph is embodied in the quote attributed to him at the end of a Jack Johnson tribute album by Miles Davis in 1970. “I’m Jack Johnson. Heavyweight champion of the world. I’m black. They never let me forget it. I’m black all right! I’ll never let them forget it!”

Labels:

Boxing,

Jack Johnson

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment