Saturday, 27 August 2016

Both Irish, both world champions, so why is Conor McGregor more famous than Carl Frampton?

Like millions around the world, I enjoy watching Conor McGregor. The guy possesses true star quality; he's articulate, funny, confident, arrogant (in a good way) - all of it combined in a package that makes for great entertainment. Moreover, after his recent victory in his rematch with Nate Diaz, he's also as tough and as brave as they come.

Yet considering the limitations of MMA when compared to boxing - i.e. brutal instead of beautiful, clumsy rather than clinical, a sport in which it is the attributes of the ploughhorse rather than the racehorse that hold sway - it has to count as a travesty that Conor McGregor is the world's best known fighting Irishman, unable to walk down any high street or main street in the Western world without being recognised, while Carl Frampton could conceivably stand outside his local supermarket for an hour or two and not be given a second look.

This gulf in profile between two professional fighters from the same island, both of whom are world champions, is not a judgment on the qualities of both sports - how could it be given that boxing is the far superior of the two? It is, however, an indictment of the lack of integrity when it comes to the money side of boxing in relation to its surplus when it comes to MMA. To put it plainly, where the UFC treats MMA fans as more than ticket and PPV fodder, the people in control of boxing have a tendency to do precisely the opposite. The result is that MMA has been allowed to occupy much of the space previously dominated by boxing when it comes to spectator interest and mainstream recognition, and losing far too many fans to its MMA rival as a result.

Just consider that magical era of great heavyweight contests of the sixties and seventies, when the best fought the best - and more than once. Does anyone seriously believe that if those legendary names - Ali, Bonavena, Chuvalo, Patterson, Liston, Frazier, Foreman, Norton, etc. - were fighting today that they'd be allowed to fight one another until the very last dollar bill had been wrung out of fights against lesser opposition? Or how about the great middleweight era of the 1980s, when the Four Horsemen - Leonard, Hagler, Hearns, and Duran - went to war against once another when they were still in their prime? The aforementioned ring greats did not place a priority on preserving an unbeaten record, nor did they go out of their way to take the easy route to the top. By doing things the hard and right way they developed and improved in ways they would never have otherwise.

Now fast forward to the highly anticipated fight between Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquaio in 2015. One thing on which every boxing fan, commentator and writer was agreed was that it was a fight that should have happened six or seven years before it did, when both fighters were in their prime, especially Pacquaio whose decline was self evident throughout a contest that did much to turn off even the most ardent follower of the sport. As for Mayweather, towards the end of his career we are talking one of the most risk averse world champions boxing has seen, focused on protecting and preserving his 'O' regardless of the quality of opposition he opted to face in the process. It was boxing as business rather than supreme test of courage, skill, movement, and will. Not that Mayweather's legacy is one to be sniffed at. As a fighter he was playing chess while his opponents were playing chequers, which meant he was hardly ever forced out of second gear. But unlike Conor McGregor vis-a-vis Nate Diaz, Mayweather never looked at a mountain in the shape of a Golovkin and felt the urge to climb it. Even when he fought Canelo he made sure it was at a catchweight that ensured the Mexican's biggest fight was not the one that unfolded in the ring but one he was forced to conduct against the scales before he stepped through the ropes.

Boxing is in desperate need of its own Dana White to clean house and reassert the primacy of the action inside the ring between the fighters over the deals and horsetrading that takes place outside between promoters and managers. The plethora of boxing sanctioning bodies have only served to diminish the status attached to a world title, while the control exerted by promoters has over time denuded the sweet science of much of its cachet value.

Something has to be done and done quickly, else a fighter of Carl Frampton's undoubted quality risks continuing to stand criminally unrecognised outside that supermarket while his compatriot, Conor McGregor, swaggers up and down the Vegas Strip like he owns the place.

Friday, 19 August 2016

Emile Griffith's struggle for respect in a man's world

It was hard enough being black in America in the 1950s and ’60s, forced to endure a daily assault on your dignity, humanity, and at times even your life. Imagine, then, what it was like to be black and gay at a time when homosexuality was a criminal offence. Then consider the particular challenges involved in being black, gay, and a boxing world champion to boot.

“God breaks those he wants to make great.”

This biblical aphorism could have been written with the remarkable life of Emile Griffith in mind. His 112 professional fights, stretching 19 years from his ring debut in 1958 to his last fight in 1977, after which he finally accepted that he had “nothing more to prove,” could never come close to competing with the struggle against adversity he fought on the other side of the ropes. For Griffith, a man whose ambition in life as a young man was never to win fame and fortune in the hurt business but to make ladies’ hats, the ring was not an arena where men risked all but rather a sanctuary and an escape from the constant pressure of concealing who he really was when he wasn’t in the gym preparing for a fight or in the ring proving himself. Award-winning sportswriter Donald McRae’s new biography of the five-time world welterweight and middleweight champion, A Man’s World, is suffused with the respect that befits someone who fought more world championship rounds, an unbelievable 337, than any other fighter in the sport — “51 more than Sugar Ray Robinson and 69 more than Muhammad Ali,” the writer informs us.

But as bad as things were outside the ring, tragedy was no stranger to Griffith in it either. Here he will forever be known for his brutal third fight against Benny “The Kid” Paret at Madison Square Garden on 24 March 1962. It was for the welterweight title that Paret had wrested from Griffith in their previous encounter and was destined to be an ugly affair from the day the contracts were signed. Paret and his team spared no opportunity to ridicule the Griffith over his sexuality, which by then was the worst-kept secret in a sport that wore its machismo as an antidote to the emasculating truths of polite society.

The insults, veiled and not so veiled, reached their nadir at the weigh-in, when in front of the large crowd of witnesses, including the press, the dread-word “maricon” (faggot) issued from Paret’s lips. As McRae describes it: “The sour taste of humiliation rose up in Emile’s throat like bile.” From that moment at stake was more than a championship belt. Now it was a matter of honour and a fight that Emile Griffith could not and would not allow himself to lose. Paret was going to pay and pay dearly, with fight night destined to be his last. During a predictably bruising war of attrition the Cuban finally succumbed in the 12th round to a barrage of unanswered right hands while slumped against the ropes, before the referee finally stepped in to stop it. It was too late. Paret never recovered. He slipped into a coma and died in hospital a week later.

Griffith never got over Paret’s death, which continued to haunt him in recurring nightmares right up to the day he died in 2013. However he had many mouths to feed and no other way of doing it than in the ring. And so he fought on — though never with the same intensity or bad intentions as before.

When he wasn’t fighting or getting ready to fight, Griffith was a regular in the underground scene of gay bars and clubs located then around New York’s Times Square. It was the only time he could relax and be himself, surrounded by friends and acquaintances that adored him. He was their champion and they protected him, made him feel there was nothing to fear or be ashamed of.

This was at a time in the early ’60s when, as McRae writes, “gay men and lesbians could be dismissed from their jobs or denied housing and other benefits on the grounds of sexuality. Their persecution was often undertaken most aggressively and systematically in New York, supposedly the country’s most liberated city.” It was a time when “over a hundred men a week were entrapped for ‘solicitation’ by undercover police, and when moral panic was regularly whipped up by ambitious politicians using the morality card in order to garner votes from a prurient and hypocritical public.”

Yes, indeed, it was no time to be gay in New York or anywhere else in the land of the free.

Even in more enlightened times, when after many years of struggle for justice homosexuality won its rightful acceptance within mainstream society, the danger had not completely passed. Griffith found this to his cost in 1992 when emerging from a gay bar in New York, he was set upon by a gang of bigots and beaten to within an inch of his life.

It was in the ring where Emile Griffith punctured the myth of and masculine stereotype that drew a false equivalence between cowardice, weakness and homosexuality. He fought all over the world under the tutelage of his close friend the legendary trainer Gil Clancy, who never left his side through good times and bad.

Towards the end of his career, in 1975, when he was reduced to fighting for a fraction of the money he could once command, Griffith took a fight in Soweto, the iconic black township in what was then apartheid South Africa. Griffith had been expecting conditions similar to those that had faced blacks in the Deep South during Jim Crow. What he found was far worse. When told by the promoter, who’d been contacted by a government official, that Clancy would not be allowed in his corner, due to apartheid laws which meant the only white men allowed in the arena in Soweto for the fight would be the police, the referee, and three judges at ringside, Griffith finally cracked. No Clancy, no fight, he informed the promoter.

The former world champion’s refusal to fight made newspaper headlines, but there was nothing to be done. The head of South Africa’s boxing board of control announced they could not intervene, but that perhaps a compromise could be reached.

Griffith responded thus: “I don’t believe in this law, and I am not negotiating. I tell you one thing straight — no Clancy, no fight. You can lock me up or send me home. I know what’s right and wrong. And this law is wrong. I refuse it.”

The fight went ahead with Gil Clancy in Griffith’s corner.

It was in 2008 that Emile Griffith was finally able to find the words to articulate the horrible hypocrisy that he was forced to bear throughout his life due to his sexuality. He told his friend, the reporter Ron Ross: “I keep thinking how strange it is. I kill a man and most people forgive me. However I love a man and many say this makes me an evil person.”

A moving epitaph to the Emile Griffith story occurred in Central Park on a winter’s afternoon in 2004, when Griffith met Benny Paret’s son, Benny Paret Jnr, who was still to be born when his father died as a result of that brutal encounter in 1962 at Madison Square Garden. The moment was caught on film for a documentary that was being made on the tragedy. Griffith approached the pre-arranged meeting place, his gait by now was that of an old man who’d had one too many ring wars, while Benny Paret Jnr stood watching him, tentative and unsure. They exchanged a few words then hugged and cried, united in the pain of a tragedy that had marked both their lives forever after.

A Man’s World by Donald McRae is published by Simon & Schuster.

“God breaks those he wants to make great.”

This biblical aphorism could have been written with the remarkable life of Emile Griffith in mind. His 112 professional fights, stretching 19 years from his ring debut in 1958 to his last fight in 1977, after which he finally accepted that he had “nothing more to prove,” could never come close to competing with the struggle against adversity he fought on the other side of the ropes. For Griffith, a man whose ambition in life as a young man was never to win fame and fortune in the hurt business but to make ladies’ hats, the ring was not an arena where men risked all but rather a sanctuary and an escape from the constant pressure of concealing who he really was when he wasn’t in the gym preparing for a fight or in the ring proving himself. Award-winning sportswriter Donald McRae’s new biography of the five-time world welterweight and middleweight champion, A Man’s World, is suffused with the respect that befits someone who fought more world championship rounds, an unbelievable 337, than any other fighter in the sport — “51 more than Sugar Ray Robinson and 69 more than Muhammad Ali,” the writer informs us.

But as bad as things were outside the ring, tragedy was no stranger to Griffith in it either. Here he will forever be known for his brutal third fight against Benny “The Kid” Paret at Madison Square Garden on 24 March 1962. It was for the welterweight title that Paret had wrested from Griffith in their previous encounter and was destined to be an ugly affair from the day the contracts were signed. Paret and his team spared no opportunity to ridicule the Griffith over his sexuality, which by then was the worst-kept secret in a sport that wore its machismo as an antidote to the emasculating truths of polite society.

The insults, veiled and not so veiled, reached their nadir at the weigh-in, when in front of the large crowd of witnesses, including the press, the dread-word “maricon” (faggot) issued from Paret’s lips. As McRae describes it: “The sour taste of humiliation rose up in Emile’s throat like bile.” From that moment at stake was more than a championship belt. Now it was a matter of honour and a fight that Emile Griffith could not and would not allow himself to lose. Paret was going to pay and pay dearly, with fight night destined to be his last. During a predictably bruising war of attrition the Cuban finally succumbed in the 12th round to a barrage of unanswered right hands while slumped against the ropes, before the referee finally stepped in to stop it. It was too late. Paret never recovered. He slipped into a coma and died in hospital a week later.

Griffith never got over Paret’s death, which continued to haunt him in recurring nightmares right up to the day he died in 2013. However he had many mouths to feed and no other way of doing it than in the ring. And so he fought on — though never with the same intensity or bad intentions as before.

When he wasn’t fighting or getting ready to fight, Griffith was a regular in the underground scene of gay bars and clubs located then around New York’s Times Square. It was the only time he could relax and be himself, surrounded by friends and acquaintances that adored him. He was their champion and they protected him, made him feel there was nothing to fear or be ashamed of.

This was at a time in the early ’60s when, as McRae writes, “gay men and lesbians could be dismissed from their jobs or denied housing and other benefits on the grounds of sexuality. Their persecution was often undertaken most aggressively and systematically in New York, supposedly the country’s most liberated city.” It was a time when “over a hundred men a week were entrapped for ‘solicitation’ by undercover police, and when moral panic was regularly whipped up by ambitious politicians using the morality card in order to garner votes from a prurient and hypocritical public.”

Yes, indeed, it was no time to be gay in New York or anywhere else in the land of the free.

Even in more enlightened times, when after many years of struggle for justice homosexuality won its rightful acceptance within mainstream society, the danger had not completely passed. Griffith found this to his cost in 1992 when emerging from a gay bar in New York, he was set upon by a gang of bigots and beaten to within an inch of his life.

It was in the ring where Emile Griffith punctured the myth of and masculine stereotype that drew a false equivalence between cowardice, weakness and homosexuality. He fought all over the world under the tutelage of his close friend the legendary trainer Gil Clancy, who never left his side through good times and bad.

Towards the end of his career, in 1975, when he was reduced to fighting for a fraction of the money he could once command, Griffith took a fight in Soweto, the iconic black township in what was then apartheid South Africa. Griffith had been expecting conditions similar to those that had faced blacks in the Deep South during Jim Crow. What he found was far worse. When told by the promoter, who’d been contacted by a government official, that Clancy would not be allowed in his corner, due to apartheid laws which meant the only white men allowed in the arena in Soweto for the fight would be the police, the referee, and three judges at ringside, Griffith finally cracked. No Clancy, no fight, he informed the promoter.

The former world champion’s refusal to fight made newspaper headlines, but there was nothing to be done. The head of South Africa’s boxing board of control announced they could not intervene, but that perhaps a compromise could be reached.

Griffith responded thus: “I don’t believe in this law, and I am not negotiating. I tell you one thing straight — no Clancy, no fight. You can lock me up or send me home. I know what’s right and wrong. And this law is wrong. I refuse it.”

The fight went ahead with Gil Clancy in Griffith’s corner.

It was in 2008 that Emile Griffith was finally able to find the words to articulate the horrible hypocrisy that he was forced to bear throughout his life due to his sexuality. He told his friend, the reporter Ron Ross: “I keep thinking how strange it is. I kill a man and most people forgive me. However I love a man and many say this makes me an evil person.”

A moving epitaph to the Emile Griffith story occurred in Central Park on a winter’s afternoon in 2004, when Griffith met Benny Paret’s son, Benny Paret Jnr, who was still to be born when his father died as a result of that brutal encounter in 1962 at Madison Square Garden. The moment was caught on film for a documentary that was being made on the tragedy. Griffith approached the pre-arranged meeting place, his gait by now was that of an old man who’d had one too many ring wars, while Benny Paret Jnr stood watching him, tentative and unsure. They exchanged a few words then hugged and cried, united in the pain of a tragedy that had marked both their lives forever after.

A Man’s World by Donald McRae is published by Simon & Schuster.

Tuesday, 16 August 2016

Whither Manny Pacquaio?

News of Manny Pacquaio's return to the ring induces sadness rather than gladness, exacerbated by the commendably frank admission by the 37-year old that the main motivation for coming back is financial. In a perfect world ring legends retire gracefully while still at the top of the sport and with the kind of financial security a successful career in boxing fully deserves. But we do not live in such a world, with Pacquaio's imminent comeback so soon after retirement yet another example of how the sweet science devours its own more often than not. It

The fight upon which Pacquaio should have retired, and upon which his legacy should have depended, was the Mayweather fight in 2015. Sadly, Manny's performance against Mayweather was so disappointing that rather than cement his legacy, it merely confirmed that he was a pale imitation of the machine that used roll over his opponents one after the other. The attempt to excuse his performance with the claim he was carrying a shoulder injury picked up in training camp, well, let's just say that it was akin to witnessing superman blaming his failure to save the world on a sore finger.

In truth is Manny Pacquiao's glory days were over well before 2015. His reign as one of the greats of his era came to a shuddering end at the hands of Juan Manuel Marquez, his ring nemesis, in the sixth round of their fourth meeting on December 8, 2012, when the Filipino southpaw walked into the kind of right hand that ends careers, in some cases lives, in an instant. The sight of him lying inert on the canvas afterwards is not one that makes a strong case for professional boxing being considered a legitimate sport.Not that there was any shame in losing to Jean Manuel Marquez. On the contrary, the Mexican was the one fighter who had Pacquiao’s number and he arguably should have won three of their four fights. Instead he lost two, drew one and won the last. They fought 42 rounds in total, which count among the most competitive ever fought in the sport.

But Pacquiao’s career cannot be judged by the Marquez fights alone. In his prime he was, as said, a ferocious fighting machine who combined frightening and fearsome power with relentless aggression. His partnership with Freddie Roach at Roach's famed Wildcard Gym in Hollywood saw them both reach the heights in their respective trades; Pacquiao recording some immense performances that will be held up as examples of excellence in years to come. The golden period of his career took place between 2006 and 2009, when the fighter affectionately known as Pacman was invincible, dispatching the likes of Erik Morales, Jorge Solis, Marco Antonio Barrera, David Diaz, Oscar De La Hoya, Ricky Hatton and Miguel Cotto. His popularity reached a new level of superstardom, especially back in The Philippines, where he was a national hero. A backstory made up of a childhood spent in extreme poverty in General Santos City only cemented his status as a people’s champion, the most meaningful title that any fighter could ever hope to achieve.

In this regard Pacquiao never forgot his beginnings or those he left behind, donating a huge proportion of his wealth to helping the poor in a country he never left behind. Indeed, though he could have opted to leave The Philippines behind for the glitz and comfort of a gated community in the Hollywood Hills, Pacquiao spent most of his time there and, of course, went into politics in order to serve his people.

Everyone knows the Mayweather fight should have happened six years before it finally did, when they were both at their peaks. The ocean of bad blood between Mayweather and his old promoter, Bob Arum, who oversaw Pacquiao’s career, ensured it never did, leaving a gap in their records that was only filled in 2015. The fight, when it came, was a crushing anti-climax, involving a way below par Pacquiao failing to force his opponent out of second gear. Regardless, despite his poor performance against Floyd, Pacquiao’s career possessed more meaning for more people than Mayweather’s ever could.

Unlike a fighter who consistently outdid himself in plumbing the depths of vulgarity in flaunting his wealth, Pacquiao fought for the have nots — the legion of migrants who make up the cleaners, valets, busboys and day labourers in the land of the free, those who exist on the flip side of the Vegas Strip, with its swanky hotels, casinos and restaurants.

Every time he stepped into the ring the Filipino carried their hopes and dreams, providing them with a temporary respite from their worries and woes, allowing them to enjoy the vicarious thrill of a champion who was of them and like them being exalted and respected in a culture in which their existence was barely acknowledged much less respected.

The Filipino champion was a symbol of pride in a world of injustice.

In this regard his greatness is unsurpassed and is why, though I wish him well, I will not be able to bring myself to watch his comeback fight against Jessie Vargas in November. As Smokin' Joe Frazier said, "Life doesn't run away from nobody. Life runs at people." Sadly, life, once so sweet, is now running at Manny Pacquaio.

Tuesday, 9 August 2016

When Ken Buchanan was King of Madison Square Garden

Not many fighters can claim to have held the unofficial title of King of Madison Square Garden during their careers. The acknowledged Mecca of boxing, New York’s Madison Square Garden in its heyday was an arena where even the most accomplished of champions and contenders were liable to be overwhelmed by the pressure of occupying its hallowed terrain. And many found themselves leaving the ring to a chorus of boos from the most hard-to-please-fans in the world in response to a lacklustre performance.

Madison Square Garden became synonymous with the sport of boxing in the over 100 years and four different locations in which it has hosted some of the most epic contests in the history of the fight game, involving the likes of John L Sullivan, Rocky Marciano, Sugar Ray Robinson, Jake La Motta, Muhammad Ali, Jerry Quarry, Joe Frazier, Roberto Duran, and Sugar Ray Leonard.

But of all the legends who’ve garnered a place in The Garden’s illustrious history, Scotland's Ken Buchanan deserves a special mention having topped the bill there not once, not twice, but a remarkable five times.

During the early 1970s, the Scottish lightweight brought to the ring the elegance of a ballerina and the heart of a pitbull. A piston jab so accurate it could have been the prototype upon which precision guided missiles were based was complemented by the contortions of an escape artist in the way he could frustrate even the most skilled attempts to lay a glove on him. It was a combination that saw him win the world title from Panama’s Ismael Laguna in 1970 over fifteen brutal rounds in the murderous heat of an outdoor arena in San Juan, Puerto Rico. In a display of guts and tenacity that even today still ranks as one of the most outstanding in the history of the ring, Buchanan announced his arrival onto the world stage.

His first appearance at The Garden in his trademark tartan shorts came just three months later in December of the same year, when the newly crowned champion fought Canadian welterweight contender Donato Paduano in a ten round non-title fight. Giving away ten pounds in bodyweight to his heavier opponent, the Scot lit up the crowd to such an extent that it rose more than once in a standing ovation in appreciation of the wonderful artistry he displayed in the process of taking his opponent to school. Watching the fight today, Buchanan ducking and weaving to avoid Paduano's punches, at times it almost appears his upper body is attached to his legs by a ball and socket instead of flesh and bone. Indeed at points during the contest he dips his head so low he could untie the laces on the Canadian's boots. In the end Buchanan emerged a comfortable winner with a unanimous decision.

His next outing at The Garden came almost exactly a year after wresting the title from Laguna, when the two met for a widely anticipated rematch. Buchanan had already defended his title twice in the interim, and by the time he stepped into the ring to meet his old rival he’d established himself as the undisputed champion. It was a contest that took on the same pattern as the first fight, with the Scotsman keeping his jab in the Panamanian’s face for fifteen rounds to win yet another unanimous decision in front of a full house.

Another Panamanian in the shape of a young Roberto Duran was Buchanan’s next challenger. Duran may have only been emerging as the legend he was to become, but already he possessed a reputation for destroying his opponents with a relentless come-forward style, throwing bombs.

The Panamanian's fight against Ken Buchanan on June 26, 1972, remains one of the most controversial The Garden has ever hosted. It began at a blistering pace, when from the opening bell Duran jumped on the Scotsman with the objective of denying him the use of a jab that by then was considered the best in the business. Duran's gameplan paid off, as within a minute of the fight Buchanan was forced to touch the canvas at the end of a right hook to take a standing eight count. If he didn’t know it already, the world champion knew now he was in for a long night.

Back he came though, trading combinations with the challenger in an attempt to keep him at bay. It was in this fashion the contest continued over thirteen bruising rounds in which Duran’s head rarely left the champion’s chest, so intent was he on fighting on the inside. The low blow that concluded proceedings came after the bell rang at the end of the thirteenth. The resulting controversy continues to be the subject of debate among boxing fans to this day. More importantly, it still rankles with Buchanan himself, who's revealed more than once in interviews that he's still reminded of it by an occasional shooting pain through the groin.

Ken Buchanan fought twice more at The Garden, recording victories against former three time world champion Carlos Ortiz and then South Korea’s Chang-Kil Lee.

His career thereafter followed the all too familiar pattern of slow but steady decline, until his eventual retirement in 1982. Nonetheless the former lightweight world champion will forever be remembered as a true ring legend and one of only a select few to ever hold the unofficial title of King of Madison Square Garden. It's one title that no one can ever take away from him - not even with a low blow.

Labels:

Boxing,

Ken Buchanan

Saturday, 6 August 2016

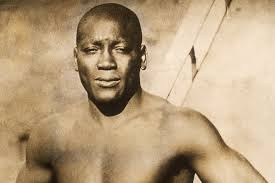

Jack Johnson - the man who wasn't afraid of anybody

On March 31 1878 in Galveston Texas a man was born who was to have a profound impact not only on the sport of boxing but on America. His name was Jack Johnson.

To be born black in late 19th and early 20th century America was to be destined for a future of low income menial jobs and the status of second class citizen at the hands of the dominant white society. It was even worse in the Deep South, where the lynching of young black men for even minor infractions of a racial divide that was as rigid as it was cruel, were a regular occurrence, it could also mean a death sentence.

Johnson’s parents were former slaves, his father Henry of direct African descent, and both worked long hours to support their six children. Jack was their second child and most of what little education he received was provided at home, where he learned to read and write. School he only attended sporadically until starting work as a labourer on the waterfornt in his early teens.

Johnson’s introduction to prizefighting came during this period, when he began taking on fellow workers and local hard men in specially organised match ups for the money offered by spectators in return for a good fight.

It has also been suggested that he participated in what were known as ‘battle royals”, a racist spectacle which involved several black men fighting one another at the same time in blindfolds. The last man standing again won a collection that was paid by the spectators in attendance.

The exact number of fights which Johnson had during his career remains under dispute, due to the fact that in his day boxing was still largely an underground sport that was illegal in many parts of the US. The least number of fights cited for him is 77, with other sources stating he fought over 100 times. Considering that boxing bouts in the early part of the 20th century could go on for thirty rounds and more, there is no disputing the immense physical ordeal he endured in a career which ended in 1938, when following the sad song of most former champions a TKO in the seventh round against an opponent who at one time would not have been fit to lace his gloves finally brought the curtain down.

But what makes Jack Johnson, who went by the fighting name the Galveston Giant, such a major figure in American sporting and cultural history was not only his undoubted boxing ability, but more a personality that brooked no deference to the prevailing racial hierarchy, one that expected blacks like him to know their place. In this he was a forerunner of another brash young black heavyweight by the name of Muhammad Ali, who cited Jack Johnson as an early inspiration.

After spending years being denied an opportunity to fight for the heavyweight title due to the colour of his skin, Johnson’s chance finally came against the Canadian holder, Tommy Burns, in 1908. Burns had taken over the title from Jim Jeffries, who’d retired and who as the champion had continually spurned Johnson’s attempts to fight for his title. Regardless, getting Burns to face him had involved two years of Johnson chasing the Canadian around the world taunting him in the press before he finally relented and agreed to face him. The fight took place in Sydney, Australia in front of a hostile crowd of 20,000 spectators.

In winning the title from Burns, even Johnson was unprepared for the wave of racial hatred that was unleashed throughout his home country. At the time the heavyweight title was deemed the preserve of white fighters, and Johnson attracted the enmity it seemed of every sector of society except his own. Even so called socialists such as famed novelist, Jack London, called for a white champion to wrest the title back from Johnson, thus spawning the era of the ‘Great White Hope’, a phrase that continues to be part of the lexicon of sports to this day.

Johnson was forced to fight a series of white contenders as the boxing establishment set out to find a white contender who would prove the physical and fighting superiority of the white man over his black counterpart. Of a series of such fights Johnson took and won in 1909, the one against Stanley Ketchel has gone down in history. The fight lasted twelve hard rounds, until Ketchel connected with a right to the head which dropped Johnson to the canvas. As he got back to his feet, Ketchel moved in to finish him off. But before he could unleash another punch he was met with a right hand to the jaw from Johnson which knocked him out. According to legend, Johnson hit Ketchel so hard that some of his teeth ended up embedded in his glove.

In 1910 the biggest heavyweight fight in the history of the sport took place in Reno, Nevada in an outdoor arena specially built for the event. Billed as ‘the fight of the century’, it saw former white champion Jim Jeffries come out of his six year retirement, saying that, “I feel obligated to the sporting public at least to make an effort to reclaim the heavyweight championship for the white race. . . . I should step into the ring again and demonstrate that a white man is king of them all.”

Johnson proved both Jeffries and the white establishment wrong, however, when he knocked the former champion down twice on the way to eventual victory in the 15th round; the referee finally stopping what had been one way traffic throughout. The aftermath saw race riots erupt across the United States, with blacks being attacked at random and during which 23 were killed. Meanwhile in black communities there were celebrations, with Johnson’s victory so significant it was commemorated in prayer meetings, poetry and black popular culture.

Thereafter, dogged by an establishment that was determined to put him in his place, Johnson’s personal life saw him tried and convicted for violation of the Mann Act, which prohibited the transportation of women across state lines for immoral purposes. Johnson, perhaps as a consequence of his being so maligned and rejected by mainstream society, was a man who sought solace in the company of prostitutes, another maligned sector of society. He was fined and sentenced to prison by an all-white jury, but instead of accepting his sentence he skipped bail and fled the country to Canada, before heading to France.

For the next seven years Johnson remained outside the US, moving between Europe and South America. In that time he continued to defend his title, though only sporadically. He finally lost it to Jess Willard in Havana in 1915. Incredibly, the fight went 26 rounds before Willard finally KO’d the reigning champion.

Returning to the US in 1920, Johnson was arrested and sent to prison to serve out his sentence. A request for his posthumous pardon is currently under consideration by President Obama. An earlier request during the previous Bush administration was turned down by the US Senate.

Johnson married three times, on each occasion to a white woman. His last wife, Irene Pineau, was asked by a reporter at his funeral what she’d loved about him. She replied, “I loved him because of his courage. He faced the world unafraid. There wasn’t anybody or anything he feared.”

Jack Johnson died at the age of 68 in 1948. Perhaps his most fitting epitaph is embodied in the quote attributed to him at the end of a Jack Johnson tribute album by Miles Davis in 1970. “I’m Jack Johnson. Heavyweight champion of the world. I’m black. They never let me forget it. I’m black all right! I’ll never let them forget it!”

Wednesday, 3 August 2016

If Brook can hurt GGG he can shock the world

Kell Brook is a man with every right to be walking around with a chip on his shoulder the size of your average mountain. Undefeated in 36 outings as a pro, 25 wins by way of KO, current holder of the IBF welterweight title, yet still he doesn't get the respect this litany of achievement deserves. Even after winning the world title he has been treated with disdain by potential opponents such as Amir Khan, who hasn't had a belt round his waist since 2012, and has failed to land the big name fights and paydays he should have way before now.

Almost as soon as the Golovkin fight was announced by Matchroom's Eddie Hearn in a deft piece of business that succeeded in leaving Chris Eubank Sr looking out of his depth in the business end of the game, an ironclad consensus among most boxing writers, pundits, and former and current fighters, was forged. Brook deserves credit for taking the fight but he doesn't stand a chance against the beast that is Gennady Glolovkin, this consensus has it, a natural middleweight with outrageous power who in 35 fights with 32 KOs has yet to be troubled, much less exposed, by anyone he's shared the ring with. The idea that Kell Brook, a welterweight, can climb the mountain involved in carrying his power with him up two weight divisions, only to then climb the other even higher mountain invovled in defeating the pound for pound unified middleweight champion, a guy who goes through his opponents one after the other like a man in a hurry to be somewhere else, is a non-starter it's so unlikely.

However this is an analysis that begins with the mistaken assumption that boxing is a sport where the difference between victory and defeat is a product of stats rather than ring craft, speed, and movement. Don't believe me? Just cast your mind back to when Leonard came out of retirement to face the Gennady Golovkin of his era, Marvellous Marvin Hagler, in 1987.

Hagler with good reason was clear favourite going into this middleweight clash in Las Vegas. Leonard hadn't fought in three years and this would be only his second bout in five years, having retired in 1982 before returning in 1984 for one fight and then retiring again. Moroeover, in his last fight he'd looked less than impressive against an opponent, Kevin Howard, who was levels below Hagler. Then there was the fact that Sugar Ray had never boxed at middleweight before, only light middleweight and welterweight.

Hagler on the other hand hadn't tasted defeat in 11 years and even though 33 he still appeared unstoppable - tough, aggressive, superfit, hungry and with power in both hands. Nonetheless, Leonard saw weaknesses while ringside at Hagler's fight against John 'The Beast' Mugabe in March 1986, who for much of the fight was able to outbox Hagler.

The key to Leonard being able to win what has gone down as one of the greatest comeback fights in the history of boxing was the way he used Hagler's aggression against him, utilising a gameplan which consisted of making Hagler miss and countering with short bursts of fast combinations and neat footwork to move out of the pocket before his opponent was able to get anything off. In refusing to war with Hagler, Leonard succeeded in frustrating him, to the point where the hitherto undefeated middleweight champion was reduced to following him round the ring like a bull chasing a matador, leaving himself open in the process.

Though Kell Brook cannot lay claim to the mantle of Sugar Ray Leonard (at least not yet), neither can Golovkin claim parity with Hagler given the names on his record. Indeed, Kell Brook is undoubtedly the best and most skilled boxer that GGG has faced, an excellent combination puncher with superb ring awareness and the ability to make adjustments. What he and his trainer, Dominic Ingle, will not make the mistake of doing is wasting energy moving round the ring in order to stay out of range, as Khan did against Canelo. This is especially vital given that Golovkin is frighteningly efficient when it comes to cutting off the ring, redolent of a young Mike Tyson as he stalks his opponents and denies them a moment's respite. Instead Brook, like Leonard, will have to get his shots off and move out of the pocket, utilising angles and constant head movement to deny his opponent the opportunity to land anything clean. Brook certainly wants to avoid finding himself on the ropes, which was the mistake Martin Murray made when he faced GGG. This is a fighter with such freakish power that even aborbing punches to the arms, shoulders and less vulnerable parts of the body is to have the fight bludgeoned out of you. Neither Brook nor Golovkin are known as speed merchants, but both compensate with superb timing and footwork, the ability to measure distance down to the last millimetre. In a fight of this magnitude those millimetres could be the difference between winning and losing.

Another performance worth weighing in favour of Brook's chances is Joe Calzaghe's against Jeff Lacy in 2006. Many expected the Welshman to lose his undefeated record against the American, who possessed considerable size and power, but Calzaghe proceeded to nullify that size and power by constantly changing the angle, throwing fast combinations before stepping off, constantly pivoting to his left to change the angle.

Kell Brook has good reason to feel confident going into this fight. His struggles and travails when it came to making 147 are well known. For a fighter to have that particular battle removed is a massive advantage, both physically and psychologically. It means he can prepare on a full tank, a factor that will tell most in sparring where it counts. Yet for all that the one unanswered question that will determine Brook's ability to shock the world is whether he has the power to hurt Golovkin. If he can do what no other GGG opponent has done in 35 fights and force him back then we're in for one hell of a battle. If not, if like all the others the Kazakh is able to walk through Brook's shots then it will only be a matter of time before he records yet another victory by stoppage.

This one unanswered question is why it would be foolish to predict with any degree of surety that Kell Brook will defeat Gennady Golovkin when they meet at London's O2. If he does it will be an achievement of historic merit, up there with a young 22-year-old Cassius Clay's stunning victory over Sonny Liston in Miami in 1964.

Tuesday, 2 August 2016

Muhammad Ali - The Lion That Roared

“I know where I'm going and I know the truth, and I don't have to be what you want me to be. I'm free to be what I want.”

A legend is born

On 26 February 1964 in Miami, not satisfied with sensationally defeating the fearsome Sonny Liston the previous night to become the youngest world heavyweight champion in history up to then, Cassius Clay has just confirmed to the assembled sportswriters and columnists that the rumours that he is a “card carrying member of the Black Muslims” are true, going on to assert his right to be “free to be what I want” in words that stand as a monument to the defiance of a preternaturally gifted boxer who would go on to make more history than any one man should be able to in three lifetimes never mind one.

With the passing of Muhammad Ali at the age of 74, after a brief battle against a respiratory illness, the world loses one of the last surviving global icons of that most tumultuous of postwar decades, the sixties, a man who along with Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Ben Bella, and Patrice Lummumba stood at the heart of the seismic political, sporting, cultural, and social events that shaped the world thereafter in so many different ways. In this illustrious company, Fidel Castro is now the only one still with us, the last living reminder of a period in history when for a brief moment hope broke free of its chains and rose up against cynicism in a determined effort to win the right to shape the future.

The legend of Muhammad Ali dwarfs the man. It begins on the day that a 12 year old boy visits a local fair in Louisville, Kentucky with a friend one summer’s day in 1954 to take advantage of the free sweets and cakes that are on offer. Whilst there the bicycle his parents just bought him for his birthday gets stolen, leaving him distraught.

Into the picture steps a local police officer by the name of Joe Martin who in his spare time runs a boxing club in the basement of the building in which the fair is being held. Martin’s attention is drawn to this distraught young boy, standing in front of him vowing to “whup” the boy who took his precious bicycle. Martin suggests that he should learn how to fight before thinking about whupping anybody and invites him to attend his boxing gym in order to do so. The legend, as they say, was born. Before leaving this story behind it is perhaps worth pausing for a moment to consider the counter factual question of what if it had not been Ali’s bicycle stolen that day but his friend’s?

Growing up in the Deep South, how could Ali not have been shaped by the racial prejudice, oppression, and apartheid Jim Crow laws legitimising segregation that obtained in this part of the world in the 1950s. It was a time when young black men like him were expected to know their place and could expect to suffer if they did not.

The extent to which the young Cassius Clay was impacted by his and his people’s treatment at the hands of a racist white establishment is measured in the racial pride and defiance he’d embraced by the time he came to public prominence. It led him to reject the received truths of his upbringing and attach himself to the Nation of Islam’s synthesis of a bastardised interpretation of Islam and black nationalism. And who better to indoctrinate Cassius with the group’s ideological and religious beliefs than Malcolm X, a legend in his own right who articulated as no other ever has the humiliation and degradation of an oppressed people?

Setting boxing on a new course

In the ring Muhammad Ali was a departure from convention in heavyweight boxing and set the division and, with it, boxing on a new course. Prior to his arrival centre stage heavyweights were typically flat footed, slow handed men with dull minds, throwing heavy ponderous punches and for the most part taking as many as they threw.

In contradistinction, Ali’s style was so outlandish for a fighter his size he was written off by every major boxing writer when he displayed it on a major stage for the first time at the 1960 Rome Olympics. Despite taking the gold in the light heavyweight division none of the boxing intelligentsia present at ringside believed he had enough power to succeed as a pro. He moved around too much, they felt, wasting energy that would inevitably see him run out of steam and wind up getting tagged. Worse, he carried his hands down at his waist when they should be up at his chin.

Ali offended their conservative sensibilities when it came to the noble art. A boxing ring was no place for flamboyance. It was an arena in which those enduring protestant values of honest endeavour and tenacity responsible for making America great were affirmed. Bad enough to witness flamboyance and braggadocio in a heavyweight fighter, but even worse they should come across it in a black heavyweight fighter.

Regardless, there was no denying Ali’s talent. His reflexes, movement, footwork and speed were extraordinary. Carrying his hands at his waist rather than up at his chin in obeisance to conventional wisdow allowed him to bend more freely at the waist, necessary when it came to slipping and pulling back from an opponent’s punches, using his head as bait to draw them before replying with stinging counters.

Married to dazzling footwork, it was a style that disoriented and frustrated every opponent he faced in the early stage of his ring career, rendering him unbeatable.

The most hated man in America and regrets over Malcolm X

The boxer known back then as the ‘Louisville Lip’ also possessed an instinct for self promotion that was ahead of its time and set the bar for future generations of hungry young contenders and champions looking to become household names. Before long he was a household name around the world, regaling the permanently huge pack of sportswriters that followed him wherever he went with a constant stream of kitsch poetry, wild predictions, and insults directed at his opponents. The staid sport of boxing had never seen anything like it. Neither had a country in which black sportsmen had become accustomed to behaving in a manner designed to ingratiate them with white America – non-threatening and passive.

Quick on the heels of Ali’s public announcement that he was a member of the Nation of Islam came the announcement that he would no longer answer to the slave name Cassius Clay and that his new name was Muhammad Ali, a name bestowed on him by Elijah Muhammad as a ploy to secure the world champion’s allegiance in his feud with former lead disciple Malcolm X. The ploy worked. Ali accepted the name and rejected Malcolm. It was a decision he would later regret while reflecting on it decades later. “I might never have become a Muslim if it hadn’t been for Malcolm,” Ali said. “If I could go back and do it over again, I would never have turned my back on him.”

Back then and overnight Ali found himself the most hated man in America. The country’s leading sportswriters lined up to heap scorn on him in their columns, reflecting popular sentiment in which Ali was disdained as an “uppity nigger”. Yet while his refusal to toe the line in the tradition of black athletes and celebrities may have earned him the enmity of many, it also earned him admiration – particularly among poor blacks – a demographic whose need for a hero had just been met with his arrival in their midst.

Here after all was a black man telling the white establishment that not only were blacks the equal of whites, they were better, and doing so years before the anti Vietnam War movement, civil rights movement, and black nationalist movements combined to produce a wave of radicalisation such as America had never experienced.

Indeed, given the extent of his defiance in the early to mid sixties it is astounding that Ali survived while the likes of John F Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Robert Kennedy were assassinated.

His attachment to the doctrine of black separation and black pride as a member of the Nation of Islam was an especially bitter pill to swallow for liberal America, which had swung behind Martin Luther King and his espousal of non violent civil disobedience in service to the cause of integration.

Vietnam

Ali’s place in history not only as a boxer but as a lightening rod for the cause of oppressed people everywhere was assured in 1967 when he refused to step forward to be inducted into the US armed forces. As he said when first notified that his draft status had been changed and he was now deemed eligible, “Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.”

This short and simple statement succeeded in invoking outrage and inspiration in equal part. In it was contained a lucid analysis of the underlying contradiction of a war being waged overseas against a poor people with dark skin by a disproportionate number of soldiers from poor backgrounds with dark skin, young men who did not enjoy equal rights in the society that was sending them to kill and die on its behalf.

The moral courage Ali displayed in refusing to be drafted remains immeasurable. Defying his own government and the nation’s political, legal, and military establishment left him isolated, especially at a time when a majority of Americans still supported the war and viewed his refusal to be drafted as an insult to the thousands of patriotic young men who had answered the call and were fighting and dying for their country. As the sportswriter Harold Conrad said: “Overnight he became a ‘nigger’ again. He threw his life away on one toss of the dice for something he believed in. Not many folks do that.”

Conrad aside, the sentiments expressed by most of the country’s leading sportswriters were scathing at best. Here for example was Milton Gross: “As a fighter, Cassius is good”, he wrote. “As a man, he cannot compare to some of the kids slogging through the rice paddies where the names are stranger than Muhammad Ali."

At this point Ali’s future appeared bleak - stripped of his title, he faced penury and five years in prison for draft evasion. And yet still he never wavered in his stance and continued to face the potential consequences of his actions with unrelenting dignity and defiance.

It was now that Ali’s opposition to the war in Vietnam was taken up by Martin Luther King, who in fastening onto the link between the racial oppression of poor blacks at home with America’s racist war against poor Vietnamese peasants overseas to reveal a political consciousness that was leading him towards class struggle and away from liberalism.

Around this time, Ali joined King at a protest in support of housing rights while on a visit to Louisville, his home town. Addressing the crowd, Ali said: “I came to Louisville because I could not remain silent while my own people, many I grew up with, many I went to school with, many my blood relatives, were being beaten, stomped and kicked in the streets simply because they want freedom and justice and equality in housing.”

Over the next three years, the now former heavyweight champion spent his time and what was left of his money locked in a legal battle to stay out of prison. Forced to surrender his passport, he was unable to leave the country to try and make a living fighting elsewhere. His enforced exile from boxing meant that his options when it came to earning money were limited to speaking engagements at college campuses.

At one such engagement in 1968 he addressed the mainly white audience of college students thus: “I’m expected to go overseas to help free people in South Vietnam and at the same time my people here are being brutalized. Hell no! I would say to those of you who think I have lost so much, I have gained everything. I have peace of heart; I have a clear, free conscience. And I am proud. I wake up happy, I go to bed happy, and if I go to jail I’ll go to jail happy.”

Few people – whether friends, associates, or members of the Nation of Islam – helped Ali while he was exiled with legal proceedings hanging over him. One man who did help him was Joe Frazier.

Frazier had won the vacant heavyweight title after it was stripped from Ali in 1967. Now he helped him with money and with various publicity stunts designed to keep Ali in the public eye, hyping up a future fight between them and lending his voice to those calling for the former champ to be allowed to return to the ring.

Return to the ring

By 1970 mainstream political and social attitudes towards the war in Vietnam had undergone a transformation. As a consequence of the resolve of the Vietnamese people, who refused to be defeated, a domestic antiwar movement that had grown exponentially, and images of the war broadcast on the nightly news that shocked more and more people with the devastation that was being visited on a poor Third World country, the war had become so unpopular it was now an albatross round the neck of the Nixon administration.

It also produced a sea change in the popular perception of Ali in the eyes of many who’d once excoriated him for refusing to be inducted. Whereas before he was widely viewed as a draft dodging traitor, now he was feted as a man of fierce principle whose stance had been both honourable and brave. Sympathetic and influential voices began calling for him to be allowed to return to the ring. The Supreme Court overturned his conviction for draft evasion in 1970 and his first comeback fight was scheduled to take place in Atlanta just a couple of months later against top heavyweight contender Jerry Quarry.

Atlanta was the home town of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, and with a large black population and a long history of racist oppression, it was a fitting location for Ali’s comeback. Even the opposition of Georgia’s governor, Lester Maddox, who attempted to have the US Justice Department block the fight, was unsuccessful. The city’s black elite had the necessary clout to have the city license the bout, buoyed by the prevailing national mood of sympathy with Ali and his stand against the war.

The excitement surrounding Ali’s return to the ring after three and half years of involuntary exile was like nothing ever seen in sport. A sold out arena and millions more at home were witness to a fight that was more akin to the national celebration and vindication of a man who three and a half years previously was facing personal ruin on a point of principle. Ali’s wheel of fortune had turned 180 degrees. Now all he had to do was prove he was still the best heavyweight on the planet and his redemption would be complete.

The burning question for sportswriters, commentators, and boxing fans was a simple one: Would the fighter who steps into the ring against Quarry after an absence of three and a half years be anything like the fighter who once electrified the sport? Quarry was a top contender and in deciding to face him in his comeback fight Ali was throwing himself in at the deep end. His years of inactivity were immediately apparent when he de-robed to reveal an increased girth.

They were confirmed after the opening bell with footwork that was markedly slower and timing that was off kilter. This was not the Ali who once devastated opponents with blinding speed and uncanny reflexes. That lithe, gangling freak of nature now appeared mortal. He still possessed his lightning whip of a jab, however, and though no longer able to step away from trouble, he compensated by tying his opponent up in clinches. The fight was stopped at the end of the third due to a cut above Quarry’s eye, but there was no denying that the win flattered Ali. He was beatable now.

A ring-style that involved holding his chin high and his right hand down by his waist, combined with a tendency to move back in straight lines, especially when he was tired, meant that Ali had always been susceptible to a left hook. Both Sonny Banks and Henry Cooper had succeeded in flooring him with the left hook during the first half of his career, when his ability to dance and move meant that most of his opponents struggled to lay a glove on him.

His lack of movement evident in a fighter who’d missed his peak due to the three and a half years he was banned from the ring, years in which his reflexes and speed had diminished, meant that he was vulnerable, available to be hit with alarming frequency by the kind of opposition that would never have troubled him previously. More significantly, for the first time Ali learned that he could take a punch - perhaps more than any fighter before or since. This realisation would prove fateful going forward into the toughest period of his career against some of the best heavyweights boxing has produced.

Rivalry with Joe Frazier

None more so in this regard was Joe Frazier. Coming in low while constantly moving his head to avoid his opponents’ punches, and with a left hook that remains one of the best in the history of the game, Frazier had the style to defeat Ali, who in turn had the style to defeat him.

The result was a trilogy of fights that rank as among the most pitiless and brutal ever seen.

The first was held at Madison Square Garden in March 1971. Dubbed the Fight of the Century, it more than matched the hype surrounding it.

Turning up at ringside by the dozen were the nation’s celebrities. Frank Sinatra filled the role of official photographer while Burt Lancaster was enlisted to help with the television commentary.

After a merciless fifteen rounds, Frazier won by unanimous decision to hand Ali the first defeat of his career. The fight was notable for the vicious left hook which Frazier landed in the last round to put Ali down on the canvas. Even more notable was the way Ali got back up within seconds of going down.

Flawed as well as great

It would be foolish not to mention dishonest and a great disservice to his legacy to try and beatify Ali as a saint when he was not. On the contrary he was all too human, flawed as well as great, a man who at various points revealed a capacity for cruelty and vindictiveness.

The manner in which he punished Ernie Terrell and Floyd Paterson in the ring for daring to call him Cassius Clay rather than Muhammad Ali have often been cited as proof of this dark side to his character. But given Ali’s political and racial consciousness, it could well be argued that by insisting on calling him by his slave name both Terrell and Paterson crossed a line and deserved the hiding they received from a fighter who by then had transcended the sport to become a symbol of resistance to the oppression of his people.

Setting those two aside, Ali is most vilified over his treatment of Joe Frazier prior to the Thrilla in Manila in 1975, the climactic and most famous fight of the trilogy they fought.

In the lead-up Ali mercilessly ridiculed, humiliated, and verbally assaulted his opponent, a man who as mentioned had helped him at a time when he stood alone as friends and former allies and supporters deserted him. In his brutal treatment of Frazier there was none of the tongue-in-cheek humour of his usual prefight antics. Ali berated him as an Uncle Tom at every opportunity, at one point even producing a toy gorilla, which he named Joe, which he punched and taunted in front of the world’s press. He described Frazier as the “white man’s champion” even though the fact that he grew up the son of a sharecropper in South Carolina, Joe Frazier’s upbringing and background made Ali’s appear aristocratic by comparison.

That being said, there is little known fact about Frazier that serves to place Ali’s treatment of him prior to their second fight into a more fitting context.

Soon after he defeated Ali and took his title in 1971, Frazier accepted an invitation to speak in front of his home state’s legislature in South Carolina. It saw him address 170 elected members of South Carolina’s political class in front of the Confederate flag, which back then still hung proud of place in the legislature’s chamber.

The irony is that neither man would have achieved the greatness they did in the ring without the other. Perhaps Ali’s need to humiliate Frazier was also a reflection of the extent to which he feared him. For there is no doubt that Smokin’ Joe was Ali’s toughest opponent, the only man he fought and described afterwards as the closest thing to death he ever experienced.

The Rumble in the Jungle

There are so many epic contests in the ring involving Muhammad Ali that it is hard to pick one out from the rest. His first fight against Sonny Liston, already mentioned, is up there, as is the Cleveland Williams fight in 1966 in which his movement in the opening round was so unreal and sublime that Williams failed to land a single punch. We also have the first and third Frazier fights; the inhuman courage he displayed in his fight against Ken Norton in 1971, ten rounds of which he fought with a broken jaw. The list goes on.

However no retrospective of Ali’s career could ever be complete without the Rumble in the Jungle, when in 1974 at the age of 36 he challenged a young, hungry, and fearsome George Foreman for his world title.

Foreman had previously knocked out Joe Frazier and Ken Norton in just one or two rounds and nobody gave Ali a prayer against him, including members of his own team. The logic seemed indisputable – Foreman had demolished Frazier and Norton, who had both defeated Ali. Surely, then, Ali was facing certain defeat. Worse, given Foreman’s awesome size and power, surely he was in danger of being seriously hurt.

Ali had long wanted to fight in Africa - to “come home” as he put it. And in the run up to the Foreman fight in Zaire, recorded for posterity in the award winning documentary When We Were Kings, Ali spared no opportunity to revel in the adulation he received in the impoverished African country. Zaire at the time was ruled by one of the most despotic and cruel dictators the developing world has ever seen in the person of Joseph Mobutu.

In 1960, as head of the army, Mobutu had toppled the left wing and pan-Africanist leader of the former Belgian colony, Patrice Lumumba, in a CIA-orchestrated coup, during which Lumumba was murdered. Mobutu was made army chief of staff by the new president, Moise Tshombe, before seizing the presidency for himself in a second coup in 1965.

Thereafter Mobutu ruled the newly created republic of Zaire with an iron fist, wherein torture, murder, and the ruthless suppression of dissent prevailed as he treated the country and its wealth as his personal possession. His motivation in staging the Rumble in the Jungle, spending millions of dollars for the privilege while millions of his people were mired in abject poverty, was to try and paint his regime in a positive light to a largely disinterested global media.

Rather than “coming home” to Africa the soon-to-be two-time heavyweight champion was inadvertently helping to recognise a ruthless US backed dictatorship.

As to the fight itself, by calling on the deep reserves of self belief that made him the unique and towering figure he was, Ali unveiled his now famous Rope-a-Dope, a tactic designed to absorb Foreman’s venom on the ropes for the best part of seven rounds, before exploding off them in the eighth to knock out him out after the younger man had punched himself out.

Never mind just boxing, the world of sport had never seen anything like it and it was entirely fitting that Ali’s greatest ever victory was witnessed by millions around the world via live telecast.

Years of physical decline

The years of Ali’s physical decline were a sad bookend to his extraordinary life. The onset of Parkinson’s was the steep price he paid for the years of glory, magic, and inspiration he gave the world. As with many fighters, the champ was unable to master himself when it came to to stepping away from the ring and the limelight. It didn’t help that he had many mouths to feed in the form of a large entourage, most of whom took far more than they ever gave.

His most public appearance in the third act of his life came at the opening ceremony of the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, when he lit the Olympic torch. Standing there in the world’s glare struggling to control his shaking limbs, the circle had closed. From charismatic and precocious boxer to black rebel and symbol of pride to his people and oppressed people everywhere, Ali had morphed into a benign figure embraced by the very establishment that once reviled him.

No matter, his life was the story of a people struggling for a sense of itself during one of the most convulsive periods in America’s history. Ali was a product of that history. It shaped him and he in turn helped shape it.

The lion that roared

Muhammad Ali lived with joy, defiance, courage, and poetry in equal measure. This is what made him so unique and one of the truly towering figures of his time. He refused to bow when bowing was the default position of his people and he spent his best years defying the odds in and out of the ring. As he said after winning the heavyweight title for the first time against Sonny Liston as a precocious 22 year old: “I shook up the world. I shook up the world!”

His greatness is not and will never be truly defined by any of the titles he won or the fame he achieved. It is and will always be defined by his willingness to endure inhuman levels of adversity for principles and beliefs that marked him out as a threat to an unjust status quo.

Muhammad Ali was much more than one of the greatest heavyweight boxers and world champions in ring history. Far more enduring will be his legacy as a champion of an oppressed people who spoke truth to power as few ever have or dared.

He truly was the lion that roared.

End.

A legend is born

On 26 February 1964 in Miami, not satisfied with sensationally defeating the fearsome Sonny Liston the previous night to become the youngest world heavyweight champion in history up to then, Cassius Clay has just confirmed to the assembled sportswriters and columnists that the rumours that he is a “card carrying member of the Black Muslims” are true, going on to assert his right to be “free to be what I want” in words that stand as a monument to the defiance of a preternaturally gifted boxer who would go on to make more history than any one man should be able to in three lifetimes never mind one.

With the passing of Muhammad Ali at the age of 74, after a brief battle against a respiratory illness, the world loses one of the last surviving global icons of that most tumultuous of postwar decades, the sixties, a man who along with Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Ben Bella, and Patrice Lummumba stood at the heart of the seismic political, sporting, cultural, and social events that shaped the world thereafter in so many different ways. In this illustrious company, Fidel Castro is now the only one still with us, the last living reminder of a period in history when for a brief moment hope broke free of its chains and rose up against cynicism in a determined effort to win the right to shape the future.

The legend of Muhammad Ali dwarfs the man. It begins on the day that a 12 year old boy visits a local fair in Louisville, Kentucky with a friend one summer’s day in 1954 to take advantage of the free sweets and cakes that are on offer. Whilst there the bicycle his parents just bought him for his birthday gets stolen, leaving him distraught.

Into the picture steps a local police officer by the name of Joe Martin who in his spare time runs a boxing club in the basement of the building in which the fair is being held. Martin’s attention is drawn to this distraught young boy, standing in front of him vowing to “whup” the boy who took his precious bicycle. Martin suggests that he should learn how to fight before thinking about whupping anybody and invites him to attend his boxing gym in order to do so. The legend, as they say, was born. Before leaving this story behind it is perhaps worth pausing for a moment to consider the counter factual question of what if it had not been Ali’s bicycle stolen that day but his friend’s?

Growing up in the Deep South, how could Ali not have been shaped by the racial prejudice, oppression, and apartheid Jim Crow laws legitimising segregation that obtained in this part of the world in the 1950s. It was a time when young black men like him were expected to know their place and could expect to suffer if they did not.

The extent to which the young Cassius Clay was impacted by his and his people’s treatment at the hands of a racist white establishment is measured in the racial pride and defiance he’d embraced by the time he came to public prominence. It led him to reject the received truths of his upbringing and attach himself to the Nation of Islam’s synthesis of a bastardised interpretation of Islam and black nationalism. And who better to indoctrinate Cassius with the group’s ideological and religious beliefs than Malcolm X, a legend in his own right who articulated as no other ever has the humiliation and degradation of an oppressed people?

Setting boxing on a new course

In the ring Muhammad Ali was a departure from convention in heavyweight boxing and set the division and, with it, boxing on a new course. Prior to his arrival centre stage heavyweights were typically flat footed, slow handed men with dull minds, throwing heavy ponderous punches and for the most part taking as many as they threw.

In contradistinction, Ali’s style was so outlandish for a fighter his size he was written off by every major boxing writer when he displayed it on a major stage for the first time at the 1960 Rome Olympics. Despite taking the gold in the light heavyweight division none of the boxing intelligentsia present at ringside believed he had enough power to succeed as a pro. He moved around too much, they felt, wasting energy that would inevitably see him run out of steam and wind up getting tagged. Worse, he carried his hands down at his waist when they should be up at his chin.

Ali offended their conservative sensibilities when it came to the noble art. A boxing ring was no place for flamboyance. It was an arena in which those enduring protestant values of honest endeavour and tenacity responsible for making America great were affirmed. Bad enough to witness flamboyance and braggadocio in a heavyweight fighter, but even worse they should come across it in a black heavyweight fighter.

Regardless, there was no denying Ali’s talent. His reflexes, movement, footwork and speed were extraordinary. Carrying his hands at his waist rather than up at his chin in obeisance to conventional wisdow allowed him to bend more freely at the waist, necessary when it came to slipping and pulling back from an opponent’s punches, using his head as bait to draw them before replying with stinging counters.

Married to dazzling footwork, it was a style that disoriented and frustrated every opponent he faced in the early stage of his ring career, rendering him unbeatable.

The most hated man in America and regrets over Malcolm X

The boxer known back then as the ‘Louisville Lip’ also possessed an instinct for self promotion that was ahead of its time and set the bar for future generations of hungry young contenders and champions looking to become household names. Before long he was a household name around the world, regaling the permanently huge pack of sportswriters that followed him wherever he went with a constant stream of kitsch poetry, wild predictions, and insults directed at his opponents. The staid sport of boxing had never seen anything like it. Neither had a country in which black sportsmen had become accustomed to behaving in a manner designed to ingratiate them with white America – non-threatening and passive.

Quick on the heels of Ali’s public announcement that he was a member of the Nation of Islam came the announcement that he would no longer answer to the slave name Cassius Clay and that his new name was Muhammad Ali, a name bestowed on him by Elijah Muhammad as a ploy to secure the world champion’s allegiance in his feud with former lead disciple Malcolm X. The ploy worked. Ali accepted the name and rejected Malcolm. It was a decision he would later regret while reflecting on it decades later. “I might never have become a Muslim if it hadn’t been for Malcolm,” Ali said. “If I could go back and do it over again, I would never have turned my back on him.”

Back then and overnight Ali found himself the most hated man in America. The country’s leading sportswriters lined up to heap scorn on him in their columns, reflecting popular sentiment in which Ali was disdained as an “uppity nigger”. Yet while his refusal to toe the line in the tradition of black athletes and celebrities may have earned him the enmity of many, it also earned him admiration – particularly among poor blacks – a demographic whose need for a hero had just been met with his arrival in their midst.

Here after all was a black man telling the white establishment that not only were blacks the equal of whites, they were better, and doing so years before the anti Vietnam War movement, civil rights movement, and black nationalist movements combined to produce a wave of radicalisation such as America had never experienced.

Indeed, given the extent of his defiance in the early to mid sixties it is astounding that Ali survived while the likes of John F Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Robert Kennedy were assassinated.

His attachment to the doctrine of black separation and black pride as a member of the Nation of Islam was an especially bitter pill to swallow for liberal America, which had swung behind Martin Luther King and his espousal of non violent civil disobedience in service to the cause of integration.

Vietnam

Ali’s place in history not only as a boxer but as a lightening rod for the cause of oppressed people everywhere was assured in 1967 when he refused to step forward to be inducted into the US armed forces. As he said when first notified that his draft status had been changed and he was now deemed eligible, “Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.”

This short and simple statement succeeded in invoking outrage and inspiration in equal part. In it was contained a lucid analysis of the underlying contradiction of a war being waged overseas against a poor people with dark skin by a disproportionate number of soldiers from poor backgrounds with dark skin, young men who did not enjoy equal rights in the society that was sending them to kill and die on its behalf.